Beauty: A Very Short Introduction by Roger Scruton

Beauty: A Very Short Introduction by Roger ScrutonMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

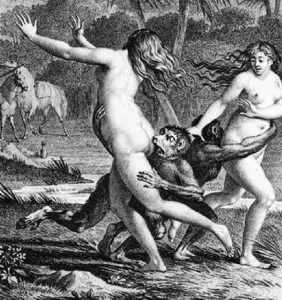

This isn’t so much a book about what beauty is as where we find it, and in what kind of traits we find it, including the question of whether all that is aesthetically pleasing is beauty (or is beauty one element among multiple sources of aesthetic pleasure.) Scruton proposes four major locations of beauty: the human form (and face,) nature, everyday objects, and art. Each of these four has its own chapter (ch. 2-5,) and those chapters form the core of the book. Other chapters examine related questions such as: whether (/how) we can judge beauty, whether it means anything to say someone has good or bad taste, and how / why we find aesthetic appeal in places often consider devoid of beauty (e.g. the profane, the kitsch, the pornographic, etc.)

I found this book to be well-organized and thought-provoking. I liked that the author used a range of examples from literature and music as well as from the graphic arts. (Though the latter offer the advantage of being able to present the picture within the book — which the book often does.) I felt that the questions were framed nicely and gave me much to think about.

Some readers will find the occasional controversial opinion presented gratuitously to be annoying, as well as the sporadic blatant pretentiousness. I forgave these sins because the overall approach was analytical and considerate.

If you’re looking for an introductory guide to the philosophy of aesthetics and beauty, this is a fine book to read. [Note: there is a VSI guide (from the same series) on aesthetics that (I assume) has a different focus (though I haven’t yet read it.)]

View all my reviews