Many years ago I was training at a dōjō that had a practitioner who was a teacher for the blind. He requested that we put together a self-defense workshop for his students. (If you’re wondering what kind of evil jackass would attack a blind person, rest assured that—sadly–such a level of jackassitude exists in the world.) The request presented an intriguing challenge. How does one adapt techniques that are premised on being able to see what the opponent is doing? Or maybe one shouldn’t adapt existing techniques but rather start from square one?

Many years ago I was training at a dōjō that had a practitioner who was a teacher for the blind. He requested that we put together a self-defense workshop for his students. (If you’re wondering what kind of evil jackass would attack a blind person, rest assured that—sadly–such a level of jackassitude exists in the world.) The request presented an intriguing challenge. How does one adapt techniques that are premised on being able to see what the opponent is doing? Or maybe one shouldn’t adapt existing techniques but rather start from square one?

In preparation for working up a lesson plan, the person that asked for the workshop briefed the black belts. We learned that very few of the blind students lived in complete darkness. Instead, they displayed a wide range of different visual impairments. He even brought a large bag of goggles that simulated various impairments so that we could train in them to better understand what would or wouldn’t work with different types of impairment.

There were goggles that had funnels over the eyes such that one could see two little circles clearly while the rest of the world was black. There were others that had a complete field of view, but had translucent tape over the lenses so that everything was reduced to fuzzy blobs—as if one were looking through Vaseline. There were lenses that had a crackle effect such that one could only see veins of area clearly. There were goggles with no peripheral vision, and ones with only peripheral vision. He also had some goggles that blacked out the world entirely. Completely blind individuals may not be as common as one would think, but they certainly exist. Putting on any of the goggles was disorienting at first. A couple of the black belts even got vertigo or nausea when they moved around too quickly.

Now imagine what it would be like if one had always had the goggles on, that it was the only worldview one had ever known. Furthermore, imagine that everyone you interacted with on a daily basis all wore the same variety of goggles. You wouldn’t see it as an affliction or a limitation. To you, your view of the world would be full and complete. You would engage in behaviors that might seem odd to an outsider with unobstructed vision (e.g. sweeping your hands around in big arcs, turning your head at unusual angles, or calling out into the “darkness”), but these behaviors wouldn’t seem odd to you because you’d know it as natural behavior for someone who experienced the world as you did. Because everyone you dealt with would see the world in the same way, it wouldn’t occur to you to think about whether there was another way to behave.

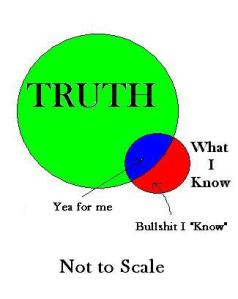

The preceding paragraph serves as an analogy for culture. One’s own culture is often invisible, especially if you don’t get outside of it much. All the people around you confirm your belief that you’re seeing the world as it is and behaving in the only natural and normal way imaginable. Sure, you may notice other people’s cultures—their skewed worldviews and the anomalous behaviors that result– but that’s because they do “strange things.” Still, some individuals will maintain that their culture doesn’t display any of the “odd” ways of behaving that more “exotic” cultures do.

But it does. Every culture is a mix of the good, the bad, and the ugly of how a people goes about living in the world given their cultural blind spots and skews. It includes collective coping mechanism for dealing with fears of uncertainty, and those are often the ugly side of culture. They encourage ingroup / outgroup separation, as well as primitive and superstitious approaches to dealing with those events, people, and behaviors that are out of the ordinary.

It’s easy to display double standards when one is blind to culture. I will give an example from my own life. It’s only been since I’ve been living in India (and traveling in Asia) that I’ve become aware of how many people are upset by Westerner’s secularization of Eastern religious / spiritual symbols and imagery. That’s a mouthful; so let me explain what I mean by “secularization of Eastern symbols and imagery.” I’m talking about “OM” T-shirts / pendants, bronze Buddhas, Tibetan thanka paintings, mandalas (on T-shirts or posters), miniature shrines, or tattoos that are purchased because they are trendy, aesthetically pleasing, or vaguely conceptually pleasing without any real understanding of the tradition from which they came or intention of honoring it.

Granted it’s easy to miss the above issue if you’re a tourist because: a.) Many of said Eastern traditions practice a live-and-let-live lifestyle that make their practitioners unlikely to be confrontational about such things (in contrast to practitioners of Abrahamic traditions (i.e. Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.)) b.) There are merchants in every country who are willing to sell anything to anybody for a buck, and so there are vast markets for tourists that offer up these symbols and images in droves.

It still intrigues me that it once caught me off guard that there were Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, etc. who were dismayed by the secularization of their traditions. I’m agnostic, but I was raised in a Christian household. Therefore, I can imagine the animosity aroused by the following conversation.

A: [Wearing a simple crucifix [or Star of David or crescent & star] pendant on a chain.]

B: Hey, A, I didn’t know you were Christian [or Jewish or Muslim]?

A: Because I’m not.

B: But you’re wearing a crucifix [or other Abrahamic symbol] pendant?

A: Oh, yeah, that. That doesn’t mean anything. It just looks cool. It’s kind of like the Nike swoosh.

B: [Jaw slackens.]

Now replace the crucifix with an “OM” shirt, and an inquiry about whether “A” is Hindu. Does it feel the same? If it doesn’t, why shouldn’t it?

Every martial art represents a subculture embedded in the culture of the place from which it came. [Sometimes this becomes a mélange, as when a Japanese martial art is practiced in America. In such cases the dōjō usually reflects elements of Japanese culture (e.g. ritualized and formal practice), elements of American culture (e.g. 40+ belt ranks so that students can get a new rank at least once a year so they don’t quit), and elements of the martial art’s culture (e.g. harder or softer approaches to engaging the opponent.)]

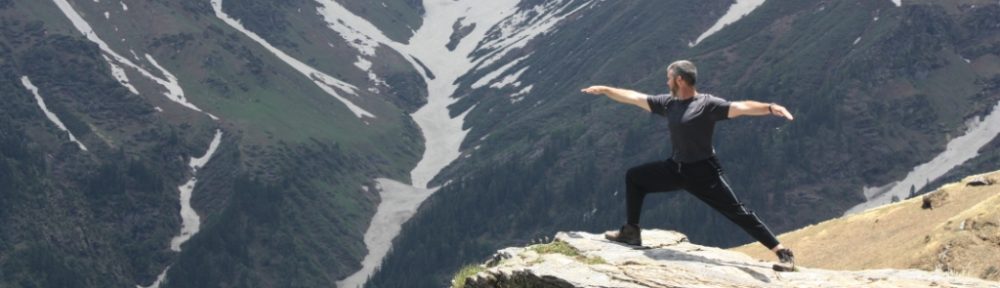

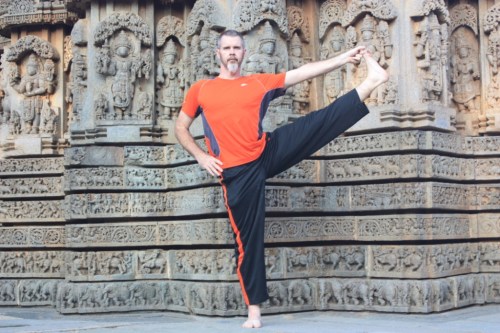

The way that culture plays into a country’s martial arts may not become clear until one has practiced the martial arts of different countries—particularly in their nation of origin. While my own experience is limited, I have practiced Japanese kobudō in America (and extremely briefly in Japan), Muaythai in Thailand, and Kalaripayattu in India. I’ll leave Muaythai out of the discussion for the time being because I can most easily make my point by contrasting Japanese and Indian martial arts. The Japanese and Indian martial arts I’ve practiced each reflects the nature of its respective culture, and they couldn’t be more different.

What are the differences between the Japanese and Indian martial arts I’ve studied? I’ve been known to answer that by saying that the Japanese martial art rarely uses kicks above waist level, while in Kalaripayattu if you’re only kicking at the height of your opponent’s head you’ll be urged to get your kick up a couple of feet higher. What does that mean? The Japanese are expert at stripping out the needless and they work by paring away excess rather than building difficulty. The impulse of the Japanese is to avoid being showy. KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) appeals to the Japanese mind. (Except for the “Stupid” part, which would be considered needlessly confrontational and gratuitously mean-spirited.) There’s a reason why Japanese martial arts don’t feature prominently in global martial arts cinema. They don’t wow with their physicality; efficiency is at the fore.

What are the differences between the Japanese and Indian martial arts I’ve studied? I’ve been known to answer that by saying that the Japanese martial art rarely uses kicks above waist level, while in Kalaripayattu if you’re only kicking at the height of your opponent’s head you’ll be urged to get your kick up a couple of feet higher. What does that mean? The Japanese are expert at stripping out the needless and they work by paring away excess rather than building difficulty. The impulse of the Japanese is to avoid being showy. KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) appeals to the Japanese mind. (Except for the “Stupid” part, which would be considered needlessly confrontational and gratuitously mean-spirited.) There’s a reason why Japanese martial arts don’t feature prominently in global martial arts cinema. They don’t wow with their physicality; efficiency is at the fore.

On the other hand, Indians are a vastly more flamboyant bunch, and Kalaripayattu is extremely impressive to watch and in terms of the physicality required to perform the techniques. The Indian art isn’t about simplifying or cutting away the unnecessary. One has to get in progressively better shape as one advances to be able to perform techniques that require one leap higher, move faster, and be stronger. The Indian art isn’t about paring away excess, it’s about making such an impressive physical display that the opponent wonders whether one is just a man, or whether one might not be part bird or lion.

On the other hand, Indians are a vastly more flamboyant bunch, and Kalaripayattu is extremely impressive to watch and in terms of the physicality required to perform the techniques. The Indian art isn’t about simplifying or cutting away the unnecessary. One has to get in progressively better shape as one advances to be able to perform techniques that require one leap higher, move faster, and be stronger. The Indian art isn’t about paring away excess, it’s about making such an impressive physical display that the opponent wonders whether one is just a man, or whether one might not be part bird or lion.

It might sound like I’m saying that the Japanese martial art is more realistic than the Indian one. Not really. Each of them is unrealistic in its own way. It’s often pointed out that the Japanese trained left-handedness out of their swordsmen, but that’s only one way in which Japanese martial arts counter individuation. Given what we see in terms of how “southpaws” are often more successful in boxing, MMA, and street fighting, eliminating left-handedness seems like an unsound tactic at the individual level. There are undoubtedly many practitioners of traditional Japanese martial arts who can dominate most opponents who fight in an orthodox manner, but who would be thrown into complete disarray by an attacker who used chaotic heathen tactics. Consider that the only thing that kept the Japanese from being routed (and ruled) by the Mongolians was two fortuitous monsoons. The samurai were tremendously skilled as individual combatants, but the Mongolians could—literally—ride circles around them in warfare between armies. Perhaps, a more relevant question is whether Miyamoto Musashi would have defeated Sasaki Kojirō if the former had followed all the formal protocols of Japanese dueling instead of showing up late, carving his bokken from a boat oar, and generally presenting a f*@# you attitude. Who knows? But as the story is generally told, Musashi’s disrespectful and unorthodox behavior threw Sasaki off his game, and it was by no means a given that Musashi would win. Some believed Sasaki to be the more technically proficient swordsman.

All martial arts are models of combative activity apropos to the needs of a particular time, place, culture, and use. And—as I used to frequently hear in academia—all models are wrong, though many are useful. (Sometimes, it’s written: “All models are lies, but many are useful.”)

[FYI: to the readers who say, “The martial art I practice is completely realistic.” My reply: “You must go through a lot of body-bags. Good for you? I guess?”]

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.