I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made: Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee, And live alone in the bee-loud glade. And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow, Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings; There midnight's all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow, And evening full of the linnet's wings. I will arise and go now, for always night and day I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore; While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey, I hear it in the deep heart's core.

Category Archives: Irish Literature

The Second Coming by W. B. Yeats [w/ Audio]

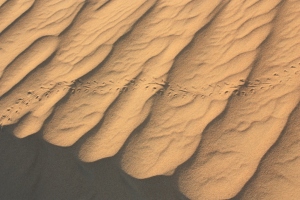

Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. Surely some revelation is at hand; Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?

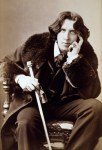

BOOKS: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar WildeMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

This is a book about what happens when you hollow out a person of all the complexity of the human condition and idealize them. At the beginning of the story, Dorian Gray is young, attractive, and preternaturally likable in a naïvely innocent kind of way. Almost to the novel’s end, through the magic of a wish made upon a portrait, Gray is still young and beautiful, though that naive innocence cracks under the strain of the impossible bifurcation of man and his soul. The artist, Basil Hallward, and Lord Henry (a man who will become a mutual friend of Gray and Hallward) cannot see Gray as a fully formed human being, but rather see him as an emblem of youth and beauty. But this unnatural ideal cannot hold, and a string of tragic deaths will be left in its wake.

The book is full of clever witticisms, albeit often of a nihilistic nature. These are almost all spoken by Lord Henry, who is the Polonius of the story – but a hipper kind of Polonius than Hamlet‘s. That said, it’s telling that toward the end of the book Gray does some of this epigrammatic philosophizing. (e.g. Such as when Gray tells Hallward, “Each of us has heaven and hell in him…”) One might dismiss this as Gray parroting Lord Henry, but I think that life has defrocked him of his naïveté, and he begins to think in ways that were impossible in his [true] youth.

This is a must-read. It’s interesting, thought-provoking, and well worth the time.

View all my reviews

Five Wise Lines from The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

All art is quite useless.

The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame.

A great poet, a really great poet, is the most unpoetical of all creatures. But inferior poets are fascinating.

You will always be fond of me. I represent to you all the sins you never had the courage to commit.

PROMPT: Cultural Heritage

It’s not something that I’ve thought of much. In my youth, I was attracted to most every culture but that of my own ancestry. In my late teens and early twenties, I visited Liverpool two or three times (just across the Irish Sea from my ancestral homeland,) but (sadly) never made it to Ireland. I’ve been to over 40 countries, but not yet my ancestral homeland. I think that’s not so uncommon to come around to an interest in such things later in life.

But the answer to the question is certainly to be found in the literature. Yeats is among my favorite twentieth century poets (if not my favorite,) and Seamus Heaney is certainly in the running. Of late, I’ve gotten on an Oscar Wilde kick, and his work definitely appeals to my ornery yet thoughtful nature. Even Joyce, who I had trouble getting into in his role as novelist, is a writer whose use of language I love.

BOOKS: Echo & Critique by Florian Gargaillo

Echo and Critique: Poetry and the Clichés of Public Speech by Florian Gargaillo

Echo and Critique: Poetry and the Clichés of Public Speech by Florian GargailloMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Out Now (May 10, 2023)

This book examines seven poets’ attempts to halt the proliferation of clichés, euphemisms, doublespeak, etc., words and phrases that not only corrupt the language but are often used to disguise bad behavior or to camouflage dismaying truths. It focuses on a technique, echo and critique, in which the poet employs one or more of these disconcerting words or phrases (or clever variants of them,) but does so in a way that reveals the chicanery within them.

The poets whose work is discussed are: Auden, Randall Jarrell, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Robert Lowell, Josephine Miles, and Seamus Heaney. These poets go head-to-head with cliché and doublespeak in the form of bureaucratese, propaganda, political speak, and business talk — with particular emphasis on war, race, and politics.

The book makes some interesting points. There are more readable discussions of the subject of corruption and manipulation of the English language, though none that I’m aware of on this particular approach to combating it. This volume is largely aimed at scholars, and not so much the popular readers. That said, I found it well worth reading.

View all my reviews

BOOK REVIEW: The Translations of Seamus Heaney by various [Trans. by Seamus Heaney / Ed. by Marco Sonzogi]

The Translations of Seamus Heaney by Seamus Heaney

The Translations of Seamus Heaney by Seamus HeaneyMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Release Date: March 21, 2023 [for the reviewed edition]

I’d read Heaney’s approachable yet linguistically elegant translation of Beowulf long ago, and was excited to see this collection of his translations coming out. The one hundred pieces gathered make for a diverse work, from single stanza poems to epic narratives and timed from Ancient Greece through modernity. The pieces include works from well-known poets such as Baudelaire, Cavafy, Dante, Brodsky, Horace, Sophocles, Ovid, Pushkin, Rilke, and Virgil. But most readers will find new loves among the many poets who aren’t as well-known in the English-reading world, including Irish and Old English poets. I was floored by the pieces by Ana Blandiana, a prolific Romanian poet who’s a household name in Bucharest, though not so well-known beyond.

I’d highly recommend this anthology for poetry readers. Besides gorgeous and clever use of language, the power of story wasn’t lost on Heaney and his tellings of Antigone (titled herein as “The Burial at Thebes,) Beowulf, Philoctetes (titled “The Cure at Troy,”) and others are gripping and well-told.

View all my reviews

BOOK REVIEW: The Critic as Artist by Oscar Wilde

The Critic as Artist: With Some Remarks Upon the Importance of Doing Nothing by Oscar Wilde

The Critic as Artist: With Some Remarks Upon the Importance of Doing Nothing by Oscar WildeMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Free to Read Online

In this dialogue, the characters of Ernest and Gilbert reflect upon the value, nature, and limits of artistic criticism. Ernest serves largely as foil and questioner, taking the everyman view that critics are failed artists and that criticism is a puny endeavor that isn’t good for much. Gilbert, on the other hand, defends criticism of art as an art unto itself, and a difficult one at that, one that requires revealing elements and ideas of the artistic piece that the artist didn’t put in the piece in the first place. Throughout, Gilbert lays down his counterintuitive bits of wisdom about the job of the critic, the characteristics of good critics, and – also – about artists and art, itself. [Ideas such as that all art is immoral.]

Oscar Wilde was famed for his wit, quips, and clever – if controversial – turns of phrase, and this dialogic essay is packed with them. A few of my favorites include:

“The one duty we owe to history is to re-write it.”

“Conversation should touch everything, but should concentrate itself on nothing.”

“If you wish to understand others you must intensify your own individualism.”

“Let me say to you now that to do nothing at all is the most difficult thing in the world, the most difficult and the most intellectual.”

“Ah! don’t say that you agree with me. When people agree with me I always feel I must be wrong.”

“…nothing worth knowing can be taught.”

This is an excellent essay, and I’d highly recommend it for anyone who’s interested in art, criticism, or who just likes to noodle through ideas. You’re unlikely to complete the essay as a convert to all of Gilbert’s tenets, but you’ll have plenty to chew on, mentally speaking.

View all my reviews

BOOK REVIEW: A Very Irish Christmas by Various

A Very Irish Christmas: The Greatest Irish Holiday Stories of All Time by Various

A Very Irish Christmas: The Greatest Irish Holiday Stories of All Time by VariousMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Out: September 14, 2021

This anthology contains fourteen previously published pieces by prominent Irish authors, including: Joyce, Yeats, and Colm Tóibín. It’s mostly short fiction, but there are a few poems as well as a couple of excerpts from longer works. All the pieces are set around (or reference) Christmas, but the degree to which that plays into the story varies a great deal. The anthology is very Irish, but not always very Christmassy. Meaning, if you’re expecting a collection of pieces like Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” where the joy or melancholy of the season is front-and-center throughout and the holiday, itself, is a pivotal story element, you won’t find that in a number of these selections. Often, the season is just an element of ambiance or of short-lived emotional resonance.

That said, the selections are all artfully written and each is intriguing in its own way. In the case of Joyce’s “The Dead” the appeal is the evocative language and creation of setting (though the piece does have more explicit story than, say, “Ulysses.”) Whereas, for pieces like Keegan’s “Men and Women” or Trevor’s “Christmas Eve” the point of interest might be the story, itself. Besides the Irish author / Christmas reference nexus, the included works cover a wide territory including contemporary works (keeping in mind the authors are mostly from the 20th century) and those that hearken back to days of yore. Some are secular; while others are explicitly Catholic.

I enjoyed this anthology, finding it to be a fine selection of masterfully composed writings.

View all my reviews