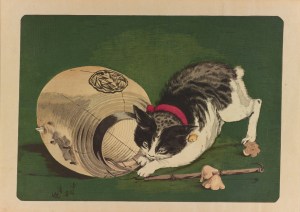

Cat & Lantern (1877) by Kiyochika Kobayashi

BACKGROUND: Issai Chozan’s Neko no Myōjutsu (“Eerie skills of the Cat”) was published in the book Inaka Sōji in 1727. It’s an example of dangibon, a light-hearted form of instructional short story, a form for which Issai Chozan is said to have been one of the originators. On the surface a story of rat-catching cats, in reality it’s a lesson in strategy and philosophy of combat.

SYNOPSIS: I’ll include citations and links below, so you can read the story in its entirety, should you choose to do so. But for now, a brief synopsis: A samurai, Shoken, has a rat in his house, and it’s driving him crazy. Shoken’s housecat is terrorized by the rat. The samurai brings in the best rat-catching cats from the neighborhood, and each is soundly defeated by the rat. Shoken decides to take matters into his own hands, chasing after the rat with a wooden sword (bokken,) but the rat evades each attempted strike and, ultimately, bites the samurai on the face. Finally, Shoken brings in a legendary elder cat from across the city, a cat who doesn’t look like much, but who effortlessly evicts the rat from Shoken’s house. The balance of the story is a conversation between the successful old cat and three of the skillful younger cats who’d failed to catch the rat (as well as with Shoken.) Each of the three explains its approach to achieving victory, and in turn the master cat explains the limitations of each one’s approach. The old master goes on to explain how when he was younger, he’d met a tomcat who slept all day, and yet no rat would come within miles of it. He asked how the tomcat achieved this, but the tomcat was unable to explain it.

THE LESSON: The first cat, a young black cat, explained that it was a master of technique. The black cat was agile and strong in movement of all kinds and practiced diligently to streamline and perfect all of its techniques. The old cat pointed out that focus on technique still left the black cat with too active a mind, thinking too much about how it would defeat its opponent. The master went on to say that there is value in technique, but it can’t be allowed to be the extent of one’s abilities. He emphasized that one’s clever actions must be in accord with the Way.

The second cat, a tabby, proudly proclaimed that all of its effort went into building its energy or spirit (ki, also called chi,) and that it could defeat most rats with a gaze (though not the one in question.) The old master explained that spirit is a fine thing but being too conscious of it hurt the second cat’s ability. The master went on to say that one can never be sure that the opponent won’t have more spirit than one, and so complete reliance on ki can lead one to a defeat.

The third cat, a gray one, said that its philosophy relied on yielding and never forcing a fight. The old master explained that this was a misunderstanding of the principle of harmony, and that this kind of yielding was a man-made contrivance that was not in accord with nature and often led to muddiness of the mind. While the old cat goes on to say that none of these elements (technique, ki energy, or yielding) is without value, it’s clear as he continues that the answer isn’t as simple as being a combination of them, but rather requires a completely new way of being, of experiencing and perceiving the world.

To Shoken, the old cat explained the importance of not thinking of swordsmanship as a means to defeat an enemy but, rather, a means of understanding life and death. The old cat went on to discuss mushin (i.e. “no mind,”) a serene state of mind that allows one to be flexible to whatever comes along. The old cat emphasized the importance of eliminating distinctions of object and subject through a process of self-realization and explained that the process of seeing into one’s being one can trigger satori (sudden enlightenment.)

CITATIONS:

Matheson Trust for Comparative Religion translation, available online at: https://terebess.hu/zen/neko.pdf

Ozawa, Hiroshi. 2005. The Cat’s Eerie Skill. Essence of Training in Japanese Culture: Technique Acquirement and Secret of Kendo. Online at: https://tenproxy.typepad.jp/recent_engagement/files/essence_of_training_in_japanese_culturee.pdf

Suzuki, D.T. 1959. The Swordsman and the Cat. Zen and Japanese Culture. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 428-435

Wilson, William Scott. 2006. The Mysterious Technique of the Cat. The Demon’s Sermon on the Martial Arts. Tokyo: Kodansha International