Diamondless Diamonds? Sounds like Daoist doublespeak or a crazy Zen koan. But, it's that which has imaginary value, but not real value. Much of what human hands reach for or produce (& which human minds obsess upon) are diamondless diamonds. People stare at them with covetous eyes, but when those eyes saccade away there's no reason to believe the diamondless diamond still exists. Eyes covet what the mind knows to have no particular worth. Diamondless Diamonds may change the world for moments at a time, but then are gone - and instantly forgotten.

Tag Archives: Thoughts

Heat Death [Common Meter]

Enlightenment in Four Bits of Shakespearean Wisdom

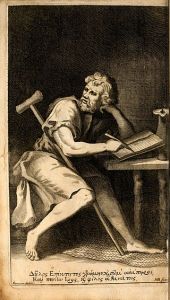

If you’re looking to attain Enlightenment, you may have turned to someone like the Buddha or Epictetus for inspiration. But I’m here to tell you, if you can put these four pieces of Shakespearean wisdom into practice, you’ll have all you need to uplift your mind.

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

william Shakespeare, Hamlet

Through Yoga, practitioners learn to cultivate their inner “dispassionate witness.” In our daily lives, we’re constantly attaching value judgements and labels to everything with which we come into contact (not to mention the things that we merely imagine.) As a result, we tend to see the world not as it is, but in an illusory form.

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

William shakespeare, julius caesar

In Psychology class, you may remember learning about the self-serving bias, a warped way of seeing the world in which one attributes difficulties and failures to external factors, while attributing successes and other positive outcomes to one’s own winning characteristics. Like Brutus, we need to learn to stop thinking of our experience of life as the sum of external events foisted upon us, and to realize that our experience is rooted in our minds and how we perceive and react to events.

The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.

william shakespeare, as you like it

A quote from Hamlet also conveys the idea, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” If you grasp this idea, you may become both humbler and more readily capable of discarding bad ideas in favor of good. It’s common to want to think of yourself as a master, but this leads only to arrogance and to being overly attached to ineffective ideas. Be like Socrates.

Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once.

william shakespeare, julius caesar

Fears and anxieties lead people into lopsided calculations in which a risky decision is rated all downside. Those who see the world this way may end up living a milquetoast existence that’s loaded with regrets. No one is saying one should ignore all risks and always throw caution to the wind, but our emotions make better servants than masters. One needs to realize that giving into one’s anxieties has a cost, and that that cost should be weighed against what one will get out of an experience.

There it is: Enlightenment in four bits of Shakespearean wisdom.

BOOK REVIEW: The Sunny Nihilist by Wendy Syfret

The Sunny Nihilist: A Declaration of the Pleasure of Pointlessness by Wendy Syfret

The Sunny Nihilist: A Declaration of the Pleasure of Pointlessness by Wendy SyfretMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

In this book length essay, Syfret proposes that the reader reconsider the much-maligned philosophy of Nietzsche, arguing not only that it needn’t lead one into a dreary morass of gloomy thinking, but that it might just help one live more in the now while escaping brutal cycles of self-punishment. She has her work cut out for her, but she doesn’t shy from the challenge. Much of what she discusses could just as easily be presented under the guise of the less melancholious brother school called Existentialism, but Syfret embraces the vilified term, at least it’s cheerier side, under the moniker “Sunny Nihilism.”

Nihilism proposes that there is no inherent “god-given” meaning to, or purpose of, life. There’s no god to create such meaning and purpose. This notion is accepted as a given by most scientifically-minded people today, but it still results in the occasional visceral dread. For cravers of meaning, the argument goes like this: at least some of life is suffering, why should I subject myself to suffering if there isn’t some grand purpose and plan.

The retort of many nihilists and existentialists goes, “You only feel that way because you’ve made mountains out of molehills through your obsession with meaning, purpose, and divine plans. The experience of being able to experience life is awesome, but you make the whole of life such a daunting prospect that anything that doesn’t turn out perfectly makes you angst-ridden. You worry far too much, and – what’s worse – you’re usually worried about the wrong things. You’re missing the freedom that comes from being able to choose for yourself what you value and to put your setbacks in perspective.”

The book also explores such related issues as: coping with the pandemic, millennial malaise, celebrity deification, and how technology and social media influence the light and the dark sides of nihilism.

I found the book to be thought-provoking, and I’d recommend it for anyone looking for a philosophy to help them live through the trials of our age.

View all my reviews

On Intrusive Thoughts & Shoving Someone in Front of a Train

The other day I read that a man had pushed a person onto the tracks in front of an oncoming train. The week before that, I'd read in a book by Robin Ince that a person who -- having had a baby thrust into his hands -- has intrusive thoughts of throwing said baby out of the nearest window is [believe it, or not] the best person to ask to hold one's baby. The argument goes like this, the person having these intrusive thoughts is being intensely reminded by his or her unconscious mind that under no circumstances -- no matter what unexpected or unusual events should transpire -- is he to throw the baby out the window (or otherwise do anything injurious.) I've heard that, at some point, virtually everyone has some type of awkward intrusive thought such as the thought of pushing a stranger in front of a train. Most never do it, nor truly want to do it. Then this one time... someone did.

Balance & the Value of Learning to Fall

I saw something sad in the park this morning. A boy was trying to learn to ride a bicycle, but I could see that he never would — not with his present approach. Why? He had one training wheel, and the bike was leaning about 15-degrees off vertical as he struggled to use the bicycle as a tricycle. I could see that the metal arm that supported the training wheel was starting to bend from the strain — thus making the lean ever more pronounced. [Incidentally, with two training wheels, I think he might rapidly learn to ride because he’d experience tipping from one side to the other, through the balance point.]

I’ve told yoga students before that there are three timelines for learning inversions (upside-down postures, which all require one’s body to learn to balance 180-degrees out of phase with the balance we all mastered as toddlers.) The first timeline is if you are willing to learn break-falls (i.e. how to safely land when — not if, it will happen — one loses balance.) If so, one can learn any inversion (that one is otherwise physically capable of performing) in an afternoon. Second, if one gets near (but not up against) a wall, and only uses the wall when one is falling towards over-rotation, then one can learn the inversion in a month — give or take. Finally, one can lean up against the wall for a million years and one will not spontaneously develop the capacity to independently do the posture. Why? Because one’s center of gravity is outside one’s body, which means one is in a perpetually unstable state, and one cannot stabilize into a balanced position from a state of falling (and leaning is just falling with a barrier in the way.)

Finding balance requires that the body be able to adjust toward any available direction to counteract the beginning of a fall in the opposite direction. I was fortunate to have studied a martial art that required learning break-falls from the outset, this made learning balances (not just inversions, but also arm balances, standing balances, etc.) much easier because there was no great concern about falling. I knew my body could fall without being injured.

Without falling there’s no learning balance, and if you only fall into the under-rotated position, you are still not learning to achieve stable balance. At some point, you will need to experience the dread fall towards over-rotation.

Time to ditch the training wheels.

POEM: Kindred Spirits [Prose Poem]

Sitting with my wife at the breakfast table this morning, I was struck by the realization that human beings and seedless watermelons have something important in common. We were both robbed of our evolutionary raison d’être, and, in both cases, the culprit was humanity (the OTHER “damned dirty ape.”)

But, at least, humans have gotten a chance to choose their new [and, hopefully, improved] reason for being. Seedless watermelons have not been so lucky.

Even imaginary monsters get bigger if you feed them

There’s a story about Epictetus infuriating a member of the Roman gentry by asking, “Are you free?”

(Background for those not into Greek and Roman philosophy. Epictetus was a Roman slave who gained his freedom to become one of the preeminent teachers of stoicism. Stoicism is a philosophy that tells us that it’s worthless to get tied up in emotional knots over what will, won’t, or has happened in life. For Stoics, there are two kinds of events. Those one can do something about and those that one can’t. If an event is of the former variety, one should put all of one’s energy into doing what one can to achieve a preferable (and virtuous) outcome. If an event is of the latter variety, it’s still a waste of energy to get caught up in emotional turbulence. Take what comes and accept the fact that you had no ability to make events happen otherwise.)

To the man insulted by Epictetus, his freedom was self-evident. He owned land. He could cast a vote. He gave orders to slaves and laborers, and not the other way around. What more could one offer as proof of one’s freedom? Of course, he missed Epictetus’s point. The question wasn’t whether the man was free from external oppressors, but whether he was free from his own fears? Was he locked into behavior because he didn’t have the courage to do otherwise?

I recently picked up a book on dream yoga by a Tibetan Lama, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. Lucid dreaming has been one of my goals as of late. I wasn’t expecting to learn anything new about practices to facilitate lucid dreaming because I’ve been reading quite a bit about the science, recently. I just thought that it would be interesting to see how the Tibetan approach to lucid dreaming maps to that of modern-day psychology. Tibetan Buddhists are–after all–the acknowledged masters of dream yoga, and have a long history of it. Furthermore, I’ve been doing research about the science behind “old school” approaches to mind-body development, lately. At any rate, it turns out that there were several new preparatory practices that I picked up and have begun to experiment with, and one of them is relevant to this discussion.

This will sound a little new-agey at first, but when you think it out it makes sense. The exercise is to acknowledge the dream-like quality of one’s emotionally charged thoughts during waking life. Consider an example: You’re driving to an important meeting. You hit a couple long red lights. You begin to think about how, if you keep hitting only red lights, you’re going to be late and it’s going to look bad to your boss or client. As you think about this you begin to get anxious. But there is no more reality in the source of your fear than there is when you see a monster in your dreams. There’s a potentiality, not a reality. Both the inevitability of being late and the monster are projections of your mind, and yet tangible physiological responses are triggered (i.e. heart rate up, digestion interfered with, etc.) It should be noted the anxiety isn’t without purpose. It’s designed to kick you into planning mode, to plan for the worst-case scenario. Cumulatively, one can get caught up in a web of stress that has a negative impact on one’s health and quality of life. For most people, when they arrive on time, they forget all about their anxiety and their bodily systems will return to the status quo, until the next time (which might be almost immediately.) Some few will obsess about the “close call” and how they should have planned better, going full-tilt into a stress spiral.

Mind states have consequences, whether or not they’re based in reality. I’ve always been befuddled by something I read about Ernest Hemingway. He’d won a Nobel Prize for Literature and was universally regarded as one of the masters of American literature, but he committed suicide because he feared he’d never be able to produce works on the level that he’d written as a younger man. There seems to be more to it than that. Many others managed to comfortably rest on their laurels when writing became hard[er]–including writers with much less distinguished careers. The monster may be imaginary, but if you feed it, it still gets bigger.

As you go about your day, try to notice your day-dreams, mental wanderings, and the emotional states they suggest. You might be surprised to find how many of them have little basis in reality. They are waking dreams.

Reflections on Vietnam

I was five when Saigon fell. So I can’t say that I remember the war as breaking news. However, by the time I was coming into adulthood, Vietnam remained front and center in the American psyche. Many of the most prominent movies on the war came out when I was in high school or shortly thereafter (e.g. Platoon (1986), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Bat 21 (1988), Casualties of War (1989), and Born on the Fourth of July (1989).) Even films that weren’t explicitly or solely about the war often featured characters transformed by its crucible (e.g. Lt. Dan from Forrest Gump.)

I was five when Saigon fell. So I can’t say that I remember the war as breaking news. However, by the time I was coming into adulthood, Vietnam remained front and center in the American psyche. Many of the most prominent movies on the war came out when I was in high school or shortly thereafter (e.g. Platoon (1986), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Bat 21 (1988), Casualties of War (1989), and Born on the Fourth of July (1989).) Even films that weren’t explicitly or solely about the war often featured characters transformed by its crucible (e.g. Lt. Dan from Forrest Gump.)

It wasn’t just cinema. While many of the most prominent books on the war came out in the 70’s and early 80’s, bestsellers were still coming out during my early adult life (e.g. The Things They Carried (1990) and We Were Soldiers Once… and Young (1992).) Even once the war wasn’t news anymore, discussion of the aftershocks continued to grace news and talk shows. I do remember my father watching an episode of 60 Minutes which showed footage of helicopters being pushed off of aircraft carriers into the sea as American forces steamed back home. I have no idea what that story was about (perhaps the ecological and environmental effects of the war,) I just thought it was too bad that they were destroying perfectly good whirly-gigs.

Terms like “the fall of Saigon” were etched into my consciousness before I had any capacity to understand them. It fell from what? To what? I didn’t know. It’s a city, right? How can a city fall? Balls fall. People fall. Dinner plates, unfortunately, fall. Of course, I’d eventually be taught what it meant, and would mistakenly think I knew what it meant for many years. I thought it meant the defeat of those forces that would keep Vietnam from becoming a totalitarian dystopia akin to the Soviet Union or, even more apropos, Kim dynasty North Korea. Sure enough, one side–the side that America had supported–had been defeated, but otherwise this “fall” was false.

As one walks around Saigon today, passing a few Starbucks, a Carl’s Jr, and innumerable Circle-Ks, it’s difficult to imagine how a victory by the other side would have resulted in a more entrepreneurial or vibrant Vietnam. The college kids at the dinner, largely ignoring the friends around them in favor of texting someone else on their iPhones, seem strikingly like their counterparts in Bangalore and Atlanta. They seem mirthful and exuberant. A tour guide lets fly little criticisms about the bureaucracy, and nobody sweeps in and throws a black hood over his head. People just don’t seem scared, brainwashed, or crazy, and–believe me–everybody who survives in North Korea fits one of those criteria. (While I’ve been impressed by cool, gregarious, and well-spoken North Korean diplomats; they’re always accompanied by a sinewy, mirthless “assistant” who I’m pretty sure has a syringe of strychnine in his pocket to silence the diplomat if he goes off script.)

As one walks around Saigon today, passing a few Starbucks, a Carl’s Jr, and innumerable Circle-Ks, it’s difficult to imagine how a victory by the other side would have resulted in a more entrepreneurial or vibrant Vietnam. The college kids at the dinner, largely ignoring the friends around them in favor of texting someone else on their iPhones, seem strikingly like their counterparts in Bangalore and Atlanta. They seem mirthful and exuberant. A tour guide lets fly little criticisms about the bureaucracy, and nobody sweeps in and throws a black hood over his head. People just don’t seem scared, brainwashed, or crazy, and–believe me–everybody who survives in North Korea fits one of those criteria. (While I’ve been impressed by cool, gregarious, and well-spoken North Korean diplomats; they’re always accompanied by a sinewy, mirthless “assistant” who I’m pretty sure has a syringe of strychnine in his pocket to silence the diplomat if he goes off script.)

I’m aware that it’s difficult to see the dysfunctions of a nation as a traveler or tourist. I also realize that–to twist Tolstoy– “All happy nations are alike; each unhappy nation is unhappy in its own way.” However, what Tolstoy’s quote doesn’t convey is that all families are unhappy in some measure–and the same is true of nations. However, it’s easy enough to see extremes of dysfunction. That’s why the Kims mostly keep foreigners out of the DPRK and carefully select and manage the experience of those they do let in. It’s difficult to imagine a degree to which things could be better in Vietnam that would have made the cost of that war worth it.

I also know that hindsight is 20/20, but where fear runs rampant foresight is 20/100 with a nasty astigmatism. In my International Affairs graduate program, I specialized in asymmetric warfare, writing a thesis entitled, “Playing a Poor Hand Well.” While my thesis didn’t focus on Vietnam, one can’t study asymmetric warfare without learning a thing or two about the Vietnam war. One learns that the mathematical, attrition rate-based formulas that analysts love are worthless in deciding a victor when one side is fighting in their backyard and the other is fighting in a place of marginal importance to a population who mostly couldn’t point said country out on a map. Will matters. What made America take on such a burden on the other side of the world? Many feared a domino effect. If Vietnam was lost to the forces of communism, soon we’d be surrounded by tyrannical totalitarian states blaring “one of us, one of us…” through loudspeakers until we relented–or something like that. In retrospect, it seems like an astounding lack of faith in the appeal of democracy and rule of law, but that’s what happens when one stews in one’s fears.

What worries me is that I still see a desire to make mountainous threats out of mere ant hills.

POEM: I Stand Before the Sea

I am a string of MEs

Strung out through eternity

But each eternity will die

Leaving in place another I

An I, a me, standing before the sea

Forget what I said about eternity

I am a finite speck of sand

Pushed and dragged by an unseen hand

Crack the speck, the TARDIS of Who

I’m every creature in the zoo

Every beast with limb and lung

Residing in every land far-flung

You think you know me? You know me not

I’ve not known me since I was just a tot

So I’ll thank you not to spoil my investigation

By classifying me by creed or nation