As I've traveled around the globe,

I've felt the music from some souls --

Those who exude, in part or whole,

a secret and sacred rhythm.

And when their tunes did call to me

I felt a yearning to be free

to dance and sing, if out of key,

yet ever so resonantly.

Who could have known that I'd go deaf.

With ear to ground, nothing was left.

It felt like a horrible theft

from all (and yet received by none.)

Tag Archives: happiness

PROMPT: Most Happy

In moments of recognition of the world’s absurdity that suggest that any response other than amusement or bemusement is purely a waste of mental energy.

PROMPT: 30 Things

1.) love; 2.) a glorious turn of phrase; 3.) discovery; 4.) walking; 5.) swimming; 6.) stumbling upon an interesting and / or novel idea; 7.) movement; 8.) travel; 9.) street food; 10.) quiet; 11.) health; 12.) recognition that when things are at their very worst, they must get better — because everything is impermanent; 13.) an intense stretch; 14.) Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass;” 15.) undiscovered country; 16.) the hanging moment; 17.) a mystery-laden world; 18.) a moment of flow; 19.) a mountain path; 20.) a clear stream; 21.) the way of non-adversariality; 22.) a thing stripped to its simplest form; 23.) the moment breath turns the tide; 24.) animals being animals; 25.) a brief instant of free fall; 26.) the recognition that something that used to cause me angst or fear no longer does; 27.) when body, movement, and the world fall into alignment; 28.) first contact with someplace / something new; 29.) connection; 30.) the first sign that the struggle is paying off.

PROMPT: Tear of Joy

Mac-n-Cheese.

But seriously, I don’t think I’m acquainted with the experience.

“Ode on Solitude” by Alexander Pope [w/ Audio]

Happy the man, whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air,

In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread,

Whose flocks supply him with attire,

Whose trees in summer yield him shade,

In winter fire.

Blest, who can unconcernedly find

Hours, days, and years slide soft away,

In health of body, peace of mind,

Quiet by the day,

Sound sleep by night; study and ease,

Together mixed; sweet recreation;

And innocence, which most does please,

With meditation.

Thus let me live, unseen, unknown;

Thus unlamented let me die;

Steal from the world, and not a stone

Tell where I lie.

PROMPT: Happy

When are you most happy?

When I allow myself to be. Hope you weren’t looking for an answer like, “Wednesdays between 4 and 7 pm.”

“Happy the Man” by Horace; Translated by John Dryden [w/ Audio]

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He who can call today his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

Tomorrow do thy worst, for I have lived today.

Be fair or foul, or rain or shine

The joys I have possessed, in spite of fate, are mine.

Not Heaven itself, upon the past has power,

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

BOOK REVIEW: Superhuman by Rowan Hooper

Superhuman: Life at the Extremes of Our Capacity by Rowan Hooper

Superhuman: Life at the Extremes of Our Capacity by Rowan Hooper

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

There are mounds of books out on the science of maximum human performance, be they on mind-hacking, sports & exercise science, or some combination thereof as applied to a particular pursuit. Hooper creates his niche by way of a broad and varied selection of topics, including: language learning, singing, running, achieving longevity, and sleeping. For the reader who is interested in the topic of how top performers in a given domain achieve that supernormal performance, it makes for an interesting read. However, it may leave some readers scratching their heads as to who the book is aimed at. It should be noted that several of the topics addressed are of much more broad-ranging appeal than those I mentioned (e.g. focus / attentiveness, bravery / courage, and resilience.)

The book is divided into three parts on “thinking,” “doing,” and “being,” respectively. The four chapters in the first part investigate the heights of intelligence, memory, language, and focus. The chapter on language deals with how some people are masterful polyglots, speaking many languages, as opposed to the harder to investigate question of how someone becomes William Shakespeare. Throughout the book, there is a mix of stories and interview insights from those who are peak performers as well as discussion of what scientific studies have found. The former makes up the lion’s share of the discussion, and the central question with of science is how much of peak performance is genetic and how much is built.

Part II, on doing, has three chapters, exploring the topics of bravery, singing, and running. This is where one really sees the book’s diversity. Books like Amanda Ripley’s “Unthinkable” address the question, among related questions, of why some act heroically, and there are a huge number of books on how to be the best runner or singer one can be, but not a lot of books take on all three questions in one section. The book on singing focuses on opera singers who belt out their tunes largely sans technology – i.e. there’s no Milli-Vanilli-ing L’Orfeo. The chapter on running gives particular scrutiny to endurance running.

Part III investigates why some people live longer, are more resilient, sleep better (or do well with less sleep,) or are happier. Since Buettner’s “National Geographic” article on “blue zones” (i.e. places where a disproportionate percentage of the population live well beyond the average human lifespan,) there’s been a renewal of interest in what science has to say about longevity. As mentioned, the chapter on sleep covers the topic from multiple vantage points. Everyone needs sleep, but some perform best with ten or more hours of sleep while others are extremely productive on four hours a day, and some can cat-nap periodically through the day while others need a single extended and uninterrupted period of sleeps. Wisely, Hooper doesn’t simply take on the question of why some people are happier than others in the book’s last chapter, but rather he asks the more interesting question of why some people who have every reason to be morose (e.g. paralyzed individuals) manage to be ecstatically happy.

The book has a references section, but there isn’t a lot of ancillary matter (i.e. graphics, appendices, etc.) It’s a text-centric book that relies heavily on stories about Formula-1 racers, opera stars, ultra-marathoners, and other extraordinary individuals while investigating the subject matter.

I enjoyed this book. I am intensely interested in optimal human performance across a range of skills and characteristics. So, I guess when people inevitably ask who the book is directed at, it’s directed at me and others with this strange fascination. If you have that interest, it’s for you as well.

5 Untruths Worth Pretending Are True

William James famously suggested that the path between emotion and expression wasn’t a one-way street. In other words, it’s not just that having an emotion causes us to express it through facial expressions and body language, but also that by assuming a given expressions we create the corresponding emotional state. James might have gone a little far in proposing the emotion can’t exist devoid of its expression, but he came by the belief that you could get to emotion through expression honestly enough.

I read about how James, suffering a bad cases of the blues, asked himself what would happen if he behaved as though he was in a happier state of mind. He decided to carry out this experiment, and he soon found himself in a much better mental state. This got me thinking about what else one might pretend that would yield positive results.

It should be noted, that there’s been a lot of research on this topic, and it’s been dubbed the “as if principle,” though colloquially people talk about it as “faking it till you make it.” Some of you may be familiar with this idea from the study showing that adopting a Wonder Woman stance made subjects feel more confident. If not, Amy Cuddy’s TED Talk can be viewed here.

So, here are five ideas–true or not–that are worth believing:

[Note: You’ve got to pretend as if you were a five-year old. Don’t bring those pathetic and puny adult imaginations.]

5.) I’m happy: Starting with the self-ruse most widely known and which James brought to our attention. You may have heard the following advice: if you’re ever feeling down, stand up and pump your fists in the air at an upward angle such that one’s body forms a “Y” (or an “X if you want to keep your feet wide.) This is a hardwired victory behavior written into our evolutionary coding, and it’s hard to be depressed while doing it.

4. Oneness / Unity: Try pretending that you’re connected to everything in the universe. The experience isn’t uncommon with mystics and meditators, as well as those in the Flow. This is an attempt to work it around from the other direction.

Now, some mystic-scientist out there is going to say that this isn’t an untruth because there’s evidence that we are connected to everything, citing quantum entanglement and such like. Maybe so, but as there’s no reason to believe we have a sensitivity to happenings at that quantum state, the pretending is still necessary. (i.e. Even if such entanglement exists, we can no more sense it than we could recognize if a force of 1-trillionth of a gram touched our skin.) Evolution doesn’t grant us capabilities beyond what are needed to survive to procreate, and so I’m doubtful that we have some untapped power to sense quantum entanglement lurking within us.) The oneness we feel has to do with the part of the brain that tracks the “I v.) not-I” divide fading out of operation–rather than an awareness of some web of subatomic entanglement.

This self-subterfuge is a way to simultaneously put one’s worries in perspective while not becoming demoralized about being an insignificant speck in a vast universe. One is an infinitesimal speck in an infinite universe, but one is tied into the universe such that one is simultaneously an infinite universe.

3.) Chi / Prana: I don’t think there’s any reason to believe that the immaterial energies of Eastern traditions (Taoism and Yoga, respectively) exist. However, I wouldn’t argue that there’s no benefit from imagining them to exist. There seems to be little doubt that visualizing the flow of these energies can have benefits–regardless of whether they’re the traditionally advertised benefits or not. Even if you don’t succeed in pulling energy into one’s body directly, sans the middlemen of food and oxygen (so one can live off the dew on a single ginko leaf–ala “Kung Fu Panda”), visualization is good for the brain and the invigorated feeling one creates in pretending chi exists can’t hurt.

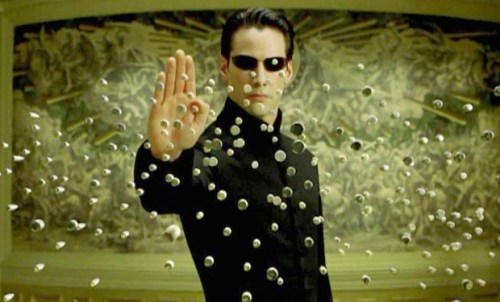

2.) “There is no spoon:” This, of course, comes from the movie “The Matrix” in which a young sage / savant attempts to teach the protagonist, Neo, how he can bend a spoon with his mind. The upshot is that one doesn’t try to bend the spoon, one realizes that the spoon is a figment of the imagination.

The idea that we are part of a simulation may turn out to be less far-fetched than it seems. I cite, for example, the TED Talk by physics Nobel Laureate George Smoot.

At any rate, the virtue of the thought exercise of pretending this is true is two-fold. First, one can ask whether one would lead the same life and give events the same weight if one was to discover that one was living out a simulation designed to advance the understanding of some entity (e.g. an alien race, a colossal supercomputer, etc.) Second–and more importantly–one may become more attuned to the fact that one’s own mental / emotional world is full of dream-like simulations. One’s brain is designed to anticipate worst-case scenarios, and it’s exceedingly good at fabricating scenarios that taint our perception of the world with anticipated negative possibilities–most of which will never come to fruition. There are many variants, attributed to various speakers, of the following Mark Twain quote:

“I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.”

1.) There is no I: A core tenet of Buddhism is that there is no self. Depending what a self has to be to exist as an independent entity, science may yet converge on a similar conclusion. The self seems, at best, to be an emergent property. In the Anil Ananthaswamy book I recently reviewed, it’s compared to a center of gravity. There’s no molecule that can be called the center of gravity, it’s a property that moves around as the body does. It’s definable, but not in terms of a specific location or physical existence.

Pretending there is no self may help put many worries into perspective. Like #4, it may also help one feel more connected to a larger world. But most importantly, it may help one to turn off those parts of one’s mind that are prone to self-loathing, self-denigration, or just self-consciousness.

Happy pretending.

BOOK REVIEW: The Geography of Bliss by Eric Weiner

The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World by Eric Weiner

The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World by Eric Weiner

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This book combines travel writing with pop science discussion of what makes people happy (or unhappy.) Weiner travels to ten countries in pursuit of happiness, and reflects upon the cultural components of bliss.

Some of the countries, like Switzerland and Iceland, rank among the world’s happiest in international surveys. Some of the countries, such as Qatar and America, have every reason to be happy, but aren’t necessarily as blissful as the rest of the world would expect. Some of them, like India and Thailand, have good reason to be unhappy, and yet they manage to be global exemplars of happiness [at least within certain domains.]

Then there are a few nations that have unique relationships to happiness. Bhutan has a national policy on happiness [plus it’s a Buddhist country, and Buddhism probably offers the most skillful explanation of what it takes to be happy of any world religion.] Moldova provides a counterweight as it’s one of the least happy countries in the world. Weiner visits the Netherlands in part because one of the biggest academic centers studying happiness is located in Rotterdam, but it also offers an opportunity to study whether the country’s unbridled hedonism (drugs and prostitution are legal) correlates to happiness. That leaves Great Britain, a country known for wearing the same happy face as its sad, terrified, and enraged faces.

I’ve been to half of the countries on Weiner’s itinerary, and—of the others—I’ve been to countries that share some—though not all—of the cultural constituents of happiness. (e.g. I haven’t been to Qatar, but I’ve been to the UAE. I haven’t been to Moldova, but I’ve seen somewhat less grim Eastern European states. I haven’t been to Switzerland or Iceland but I’ve been to cold countries in Western Europe. I haven’t been to Bhutan, but I’ve been in areas where Tibetan Buddhism was the dominant cultural feature.) This allowed me to compare my experiences with the author’s, as well as to learn about some of the cultural proclivities that I didn’t understand during my travels. And I did find a lot of common ground with the author, as well as learned a lot.

I found this book to be interesting, readable, and funny. Weiner has a wacky sense of humor that contributes to the light-hearted tone of the book—perfect for the subject. That said, some people may be offended because the author doesn’t pull punches in the effort to build a punchline, and this sometimes comes off as mocking cultures. However, in all cases—even that of Moldova—Weiner does try to show the silver lining within each culture.

The paperback edition I read had no graphics or ancillary matter. There are no citations or referred works (except in text), and the chapters are presented as journalistic essays. The chapters largely stand alone, and so one could read just particular countries of interest. He does refer back to events that happened in earlier chapter or research that related to another country’s cultural proclivities, but not often. The first chapter, on the Netherlands, would be a good one to read first because he describes many of the scientific findings on happiness in that one.

I would recommend this book for anyone interested in what makes some places happier (or sadder) than others.