Some keep the Sabbath going to Church --

I keep it, staying at Home --

With a Bobolink for a Chorister --

And an Orchard, for a Dome --

Some keep the Sabbath in Surplice --

I, just wear my Wings --

And instead of tolling the Bell, for Church,

Our little Sexton -- sings.

God preaches, a noted Clergyman --

And the sermon is never long,

So instead of getting to Heaven, at last --

I'm going, all along.

Category Archives: Spirituality

PROMPT: Spirituality

If by “spirituality” one means some kind of attachment to the supernatural, then not at all important. If by “spirituality” one means experiencing the world with a sense of awe, wonderment, and unmitigated bliss, then very important.

BOOK: “The Perennial Philosophy Reloaded” by Dana Sawyer

The Perennial Philosophy Reloaded: A Guide for the Mystically-inclined by Dana Sawyer

The Perennial Philosophy Reloaded: A Guide for the Mystically-inclined by Dana SawyerMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Release Date: July 9, 2024

The good news is that this book does a thorough, clear, and balanced job of discussing Perennial Philosophy along a number of dimensions including metaphysics, psychology, theology, and aesthetics. The bad news is that it can lead one to believe there IS NO Perennial Philosophy, just a hodge-podge of (often disparate) assumptions about the grand metaphysical questions of life, the universe, and everything, assumptions that are usually Eastern, mystical, or both and which appeal to the kind of person who likes to say, “I’m spiritual, but not religious,” but which are all over the place, intellectually speaking. We learn more about the varied metaphysical perspectives that can be lumped under rubric Perennial Philosophy, than we learn of any internally consistent set of beliefs which distinguish the Philosophy from others. Sawyer does acknowledge that there is not a unified worldview that is Perennial Philosophy and that, instead, one must think in terms of “family resemblance.” The problem is that Perennial Philosophy displays the kind of family resemblance seen in a foster home. One can believe in a god or not, believe in a soul / persistent self or not, one can hold any number of beliefs about time, causation, creation, and other aspects of metaphysics. Sawyer does solidly distinguish Perennial Philosophy from Materialism, but it’s not clear why we needed it, given we already had various permutations of Idealism.

The book does provide a lot of food-for-thought, if often frustratingly so. The most important thing it does is lay out the various questions at the fore of Perennial Philosophy, how they’ve been addressed by different thinkers, and the crux of discord.

I did find myself disturbed by the arguments on occasion. A prime example is when Sawyer writes about students who describe themselves as non-spiritual but who enjoy going hiking. Because Sawyer couches the experiences that are had on a good hike in spiritual terms, he believes the students are wrong to describe themselves as “non-spiritual.” However, it’s far from clear why they need to twist their interpretations into line with his worldview. I suspect that his “non-spiritual” students, like me, see in “spiritual” types a need to escape the surly bonds of nature, to have magic exist in their worlds, something above and beyond nature. I see “spiritual” people as having a craving like the proverbial true-believer / flood victim whose neighbors come by in a truck and a boat to rescue him (and then rescue services come by with a helicopter,) but he turns them all down because “God Will Save Me!” Then he dies and goes to heaven and berates God for letting him drown, to which God says, “I sent a truck, a boat, and a helicopter. What do you want from me?” Well, he wanted a divine golden light to levitate him not some mundane solution based in the natural world; he wanted magic, rapturous rescue.

If you are interested in the various debates between Materialism and Idealism, this book is well worth reading, and if you describe yourself as “Spiritual, but not religious,” you’ll probably really love it.

View all my reviews

BOOKS: “One Hundred Poems of Kabir (1915)” Translated by Rabindranath Tagore

One Hundred Poems of Kabir by Kabir

One Hundred Poems of Kabir by KabirMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Kabir was a fifteenth century Indian poet and mystic. This collection was translated by the Bengali Indian Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, and Tagore’s stylistic imprint is felt in these poems. The poems are overwhelmingly of a mystic / spiritual nature. Kabir was non-sectarian but extremely oriented towards mystic belief. He references the Koran and Vedas alike, but is more likely to communicate in secular, if mystical, terms.

How much the godly emphasis works for the reader will vary greatly. For me it was a bit excessive, often reading more like prayers than poems, but your results may vary.

The only thing I found actually disturbing was the repeated romanticization of sati, a practice in use during Kabir’s lifetime in which widows would be burned alive on their husband’s funeral pyre. Kabir repeatedly writes of sati as if it was always a completely voluntary act of raw passion and connection and was never motivated by being old and destitute (not to mention being societally pressured or, even, physically forced into it.)

The poems are well composed and engaging, and if you can get past the periodic sati propaganda, it’s a pleasant, almost euphoric, read.

View all my reviews

Mystic Limerick

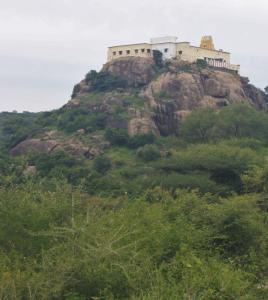

Temple on a Hill [Free Verse]

granite bubbled out of the jungle, and - upon it - they built a temple its walls were anchored into stone until its walls were the hill, and the hill was its walls and no one could find one true point at which one ended & the other began was it built to be closer to the heavens, or further from hell? not by people for whom heaven & hell reside in the mind -- unattainable by velocity, inescapable by distance -- constant traveling companions only confronted head-on maybe they wanted it to feel permanent, knowing even that granite would crumble in due time

BOOK REVIEW: Miracles: A Very Short Introduction by Yujin Nagasawa

Miracles: A Very Short Introduction by Yujin Nagasawa

Miracles: A Very Short Introduction by Yujin NagasawaMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

This concise guide to miracles is built around the intriguing observation that, according to polls, a majority of people believe in miracles, and yet we don’t witness supernatural events [at least not ones that can be confirmed by objective investigation.] There are coincidences (boosted in salience by selection bias and / or a lack of intuitive grasp of probability,) there are patterns that our minds turn into significant images (e.g. the Madonna on a taco shell,) and there are cases of spontaneous remission in which a serious medical condition disappears where treatments haven’t worked or weren’t tried (experienced by the devoutly religious, the marginally religious, the agnostic, and the atheistic, alike.) But those events can be explained more simply without resorting to the supernatural (i.e. probability, the human brain’s great skill at pattern recognition [re: which is so good that it often becomes pattern creation,] and the fact that under the right circumstances the human body’s immune system does a bang-up job of self-repair.)

The five chapters of this book are built around five questions. First, what are miracles – i.e. what criteria should be used, and what events that people call miracles fail to meet these criteria? Second, what are the categories of miracles seen among the various religious traditions [note: the book uses examples from both Eastern and Western religions, though generally sticks to the major world religions?] Third, how can one explain the fact that so many believe despite a lack of evidence? This chapter presents hypotheses suggesting we’re neurologically wired to believe. Fourth, is it rational to believe? Here, philosophers’ arguments (most notably and extensively, that of Hume) are discussed and critiqued. The last chapter asks whether non-supernatural events can (or should) be regarded as miraculous, specifically acts of altruism in which someone sacrificed their life for strangers.

I found this book to be incredibly thought-provoking, and it changed my way of thinking about the subject. I’d highly recommend it.

View all my reviews

In Praise of Multiplicity [Free Verse]

Everybody seeks oneness, but maybe one with everything is too much, it's a state in which one is lost, irrelevant, and unloved - all at once. Maybe it's better to be tied to the mast - like Odysseus - straining to make that dangerous connection, but unable to, the connection of non-connection, the love of longing, of trying, but not of being plugged in -- air-gapped to prevent resonance at a frequency that would shatter one's soul.

BOOK REVIEW: Sonnets by Sri Aurobindo

Sonnets by Sri Aurobindo

Sonnets by Sri Aurobindo

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This booklet collects together the 88 sonnets written by Sri Aurobindo. Aurobindo was a guru who set up his ashram in Pondicherry because he was on the lam from the Brits, and Pondicherry was under French control at the time. Sri Aurobindo is a karma yogi (yogi of action and good works) who – together with a partner who the community came to call “Mother” – set up Auroville with the intention of making it a utopia.

The eighty-eight sonnets are arranged in two parts. The first seventy-four were written in the 1930s and 40s, and part II consists of 14 sonnets that were written between 1898 and 1909. The sonnets of the first part are more mystical and also more stream of consciousness. The poems of Part I use vivid language, but aren’t always easy to follow – if one is seeking a coherent meaning from each. The sonnets of part II are less sophisticated (and more easily interpreted) and feature a degree of angst that is completely absent in the latter poems (latter chronologically, earlier in the volume.) The sonnets presented are in varying styles. While they are all fourteen lines of pentameter, the rhyme scheme varies.

At the end of the book there are notes on the collection as a whole, as well as short notes on individual poems. There is also a short section in the back that shows a few of the poems under edits so that one can gain a little insight into the poet’s sausage-making process.

I found these poems intriguing to read. As I suggested, they aren’t always easy to interpret but they have a thought-provoking spirituality to them as well as some beautiful use of language. One needn’t necessarily have an interest in Sri Aurobindo to enjoy the poems, although they are overwhelmingly of a mystical / spiritual nature.

BOOK REVIEW: Two Saints by Arun Shourie

Two Saints: Speculations Around and About Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Ramana Maharishi by Arun Shourie

Two Saints: Speculations Around and About Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Ramana Maharishi by Arun Shourie

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I suspect this book is extremely controversial for many, though it echoes many of my own views. The central premise of the book is that there is a middle ground position between: a.) true believers who insist that gurus and god-men hold superpowers and can perform miracles, and b.) rational skeptics who hold that god-men are inherently frauds and their followers are necessarily either shills or dunces.

What is this middle way? First of all, it denies the existence of the supernatural and rejects the premise that certain men and women — through great virtue or intense practice — can circumvent the laws of physics. (Which isn’t to suggest that great virtue and intense practice can’t have profound impacts on a person and the community in which he or she resides.) Secondly, on the other hand, it acknowledges that scientific findings (or at least feasible hypotheses) on matters such as out-of-body experiences (OBE,) hypnotic trances states, hallucinations, epileptic seizures, the placebo effect, and near-death experiences (NDE) can offer insight into how rational, intelligent, and good-natured individuals might develop a belief in the supernatural. There is a third premise that is implicit throughout Shourie’s discussion of the life and works of these two great teachers (also which I share), which is that a lack of superpowers in no way detracts from what these two great gurus achieved.

As the subtitle suggests, the author is merely speculating as there is no way to put these ideas to the test, given these individuals are long deceased and (unlike, say, the Dalai Lama) would be unlikely to show an interest in such explorations even if they were alive. However, Shourie seeks to systematically demonstrate connections between the events described by the holy men and their followers and what scientific papers have described with respect to studies of unusual phenomena like OBE, NDE, and hallucinations. (e.g. it’s long been known that with an electrode applied to the right place on the brain a neuroscientist can induce an OBE in anyone. The widespread accounts of this feeling /experience that one is rising out of one’s body, often by respectable individuals of impeccable character, is one of the reasons for believing there must be an immaterial soul that is merely carted about by the body.)

The titular two saints that Shourie makes the centerpiece of his inquiry are the Bengali bhakti yogi Sri Ramakrishna and the jnana yogi from Tamil Nadu, Sri Ramana Maharshi. [For those unfamiliar with the terms “Bhakti Yogi” and “Jnana Yogi,” the former are those whose practice emphasize devotion and worship while the latter are those whose practice emphasize self-inquiry and study. The third leg of the stool being “Karma Yogis,” who focus upon selfless acts is the core of their pursuit of spirituality.] These two teachers were both born in the 19th century, though Sri Ramana lived through the first half of the 20th century. Besides being widely adored and seen as holy men of the highest order, they also serve as a kind of bridge between the ancient sages who lived out simple lives of spirituality in destitution and the modern gurus who often have vast commercial enterprises ranging from hair-care products to samosa mix all run from ashrams that are similar to academic universities in scope and grandeur. Some might argue that Ramakrishna and Ramana were the last of their kind in terms of being internationally sought after as teachers while not running an international commercial enterprise. Another way of looking at it is that they are modern enough that the events of their lives are highly documented, but not so modern as to have the taint modernity upon them.

The book is organized over sixteen chapters, and is annotated in the manner of scholarly works. The early chapters delve deeply into the life events of these two men, and in particular events that are used as evidence of their miraculousness. Through the middle, the author looks at how events in these individual’s life correspond to findings in studies of subjects such as the placebo effect (ch. 10,) hallucinations (ch. 7, e.g. given sleep or nutritional deprivation,) and hypnotic suggestion (ch. 9.) Over the course of the book, the chapters begin to look more generally at questions that science is still debating, but which are pertinent to spirituality – e.g. what is the nature of the self (ch. 12), what is consciousness? (ch. 13), and what does it mean for something to be real (ch. 15.) The final chapter pays homage to these two saints.

I found this book to be highly thought-provoking and well-researched. Shourie is respectful of the two teachers, while at the same time insisting that it’s not necessary for them to be super-powered for them to be worthy of emulation, respect, and study. I’d highly recommend this book for anyone interested in the questions of mystical experience and the scientific insights that can be offered into it.