The Holocaust and other killings of massive scale (e.g. Cambodia’s Killing Fields, Stalin’s Great Purge, etc.) How does villainy triumph on such vast scales? Is there something in our nature that’s just not right, that’s ripe for lunacy under some conditions? What the hell is wrong with humanity?

Tag Archives: Holocaust

FORCED MARCH by Miklós Radnóti [w/ Audio]

Crazy. He stumbles, flops, gets up, and trudges on again. He moves his ankles and his knees like one wandering pain, then sallies forth, as if a wing lifted him where he went, and when the ditch invites him in, he dare not give consent, and if you were to ask why not? perhaps his answer is a woman waits, a death more wise, more beautiful than this. Poor fool, the true believer: for weeks, above the rooves, but for the scorching whirlwind, nothing lives or moves: the housewall's lying on its back, the prunetree's smashed and bare; even at home, when darkness comes on, the night is furred with fear. Ah, if I could believe it! that not only do I bear what's worth the keeping in my heart, but home is really there; if it might be! -- as once it was, on a veranda old and cool, where the sweet bee of peace would buzz, prune marmalade would chill, late summer's stillness sunbathe in gardens half-asleep, fruit sway among the branches, stark naked in the deep, Fanni waiting at the fence blonde by its rusty red, and shadows would write slowly out all the slow morning said -- but still it might yet happen! The moon's so round today! Friend, don't walk on. Give me a shout and I'll be on my way.

Bolond, ki földre rogyván fölkél és ujra lépked, s vándorló fájdalomként mozdít bokát és térdet, de mégis útnak indul, mint akit szárny emel, s hiába hívja árok, maradni úgyse mer, s ha kérdezed, miért nem? még visszaszól talán, hogy várja őt az asszony s egy bölcsebb, szép halál. Pedig bolond a jámbor, mert ott az otthonok fölött régóta már csak a perzselt szél forog, hanyattfeküdt a házfal, eltört a szilvafa, és félelemtől bolyhos a honni éjszaka. Ó, hogyha hinni tudnám: nemcsak szivemben hordom mindazt, mit érdemes még, s van visszatérni otthon, ha volna még! s mint egykor a régi hűs verandán a béke méhe zöngne, míg hűl a szilvalekvár, s nyárvégi csönd napozna az álmos kerteken, a lomb között gyümölcsök ringnának meztelen, és Fanni várna szőkén a rőt sövény előtt, s árnyékot írna lassan a lassu délelőtt, -- de hisz lehet talán még! a hold ma oly kerek! Ne menj tovább, barátom, kiálts rám! s fölkelek!

NOTE: Originally titled, ERŐLTETETT MENET, and dated September 15, 1944 (in Bor, Serbia,) this poem was found on Radnóti’s person after his execution by fascists in 1944. The translation used is that of Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner: i.e. Radnóti, Miklós. 2014. Foamy Sky: The Major Poems of Miklós Radnóti. ed. & trans. Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner. Budapest: Corvina Books, pp. 228-229.

PROMPT: Historical Event

What historical event fascinates you the most?

It varies over time. For a long time, it was the Second World War and the Holocaust. How do you get the rise of Nazis and the horrors that sprang therefrom? Sadly, I think that question has been answered to my — for lack of a better word— satisfaction.

The execution of Socrates has spurred a great deal of thought.

In terms of what is not so much a historical event, but historical processes, I’m intrigued by the life of Buddha.

Then there are a lot of explorer / adventurer travels.

BOOK REVIEW: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael ChabonMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Escaping 1939 Prague, Joe Kavalier moves in with family in Brooklyn, becoming fast friends with his younger cousin, Sam Clay. Combining their talents, Joe as artist and Sam as writer, the young men create a number of popular comic book characters. For those unfamiliar with comic book history, a major stream running through this story involves the trials of “work for hire.” Because of the nature of comic book publishing, creative types tended to work on salary (giving the publisher all rights to whatever was created – e.g. TV shows, toys, etc.) Because of this, the creators of some of the most lucrative characters and stories received little credit or financial reward (relative to the profits.) While these artists / authors didn’t lose their shirt if a title failed, there’s something offensive about Corporations (or actors) shoveling in money from a franchise while the creator lives a dank suburban existence.

If it were just about the unfair lives of comic book creators, the book would be interesting — but not 600+ pages interesting. What makes this a compelling story is that each of the titular characters has a darker challenge with which to deal. For Joe, it is an obsession with bringing as much of his family to safety as he can, and coping with his rage against the Nazis. For Sam, it is the fact that he is a closeted and conflicted gay man in 1940’s and 50’s America. The driving question is whether the two men will be able to avail themselves of the tripartite support network (themselves, plus Rosa – Joe’s girlfriend,) or whether either (or both) will self-destruct because of an inability to do so.

This is a well-crafted novel and I highly recommend it.

View all my reviews

BOOK REVIEW: Freiheit! by Andrea Grosso Ciponte

Freiheit!: The White Rose Graphic Novel by Andrea Grosso Ciponte

Freiheit!: The White Rose Graphic Novel by Andrea Grosso Ciponte

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Out: March 4, 2021

This tragic story tells the tale of a small college-centric anti-Nazi resistance group, doing so in graphic novel form. While it touches upon the story of six White Rose members who were executed, special emphasis is given to the sister-brother duo of Sophie and Hans Scholl. White Rose was largely involved in distributing leaflets to encourage others to engage in resistance activities against the Nazis. (Note: the translated text of the White Rose pamphlets is included as an appendix.) There is so much attention given to the truly fascinating question of how a bunch of fascist lunatics managed to run a country into such diabolical territory that it can easily be missed that there was at least some resistance within Germany. I, for one, was oblivious to the story of White Rose before reading this book.

The arc of the story takes the reader from the upbeat stage during which White Rose was succeeding in distributing articulate and persuasive flyers, through some of their close calls and other frustrations (e.g. the Scholl’s father being arrested), and on to the bitter end. Much of what I’ve seen previously about resisters centered on communists. One sees in White Rose a different demographic. There are a number of religious references without the “workers of the world unite” lead that would be taken by leftist groups.

I believe the author overplayed the stoicism with which the executed individuals accepted their fate. This is based upon a true story, and so this may seem an unfair criticism because perhaps that’s how it appeared in reality. However, from a storytelling perspective, it felt surprisingly devoid of emotional content [given the events provide loads of potential for it.] There is a great tragedy in young people being executed by the State for asking others to resist fascism, but as a reader I didn’t really feel an intense visceral connection to events. As I said, I suspect this had to do with the author wishing to show that the Scholls took it in all in stride, but I think some display of angst or anger might have made for a more intense reading experience. I don’t know whether it was more a textual or graphic issue that left me unmoved.

All in all, the book was an interesting insight into resistance to the Nazis in an academic environment. I did find reading the pamphlet translations themselves to be insightful. The flyers give one insight into where the student-resisters were coming from, and what buttons wished to push in others. It might have been a bit more gripping, but it was an interesting telling of events.

If you’re interested in learning more about Germans who resisted the fascists, this book provides a quick example of how (and by whom) it was done, and I’d recommend you give it a read.

BOOK REVIEW: The Photographer of Mauthausen by Salva Rubio

The Photographer of Mauthausen by Salva Rubio

The Photographer of Mauthausen by Salva Rubio

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Due out: September 30, 2020

This “graphic novel” tells the story of a Spanish photographer, Francisco Boix, who was sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp as a Communist during the Second World War. [Note: I only put graphic novel in quotes because it’s not a fictitious story, which “novel” implies, but graphic novel seems to be the accepted term for any graphically depicted story – fact or fiction.] Mauthausen was a camp in Austria. While it wasn’t technically one of the extermination camps, it was legendary for the death toll associated with the granite mine where many of the inmates labored. Its “staircase of death” was the location of untold fatalities, including: murders by the Nazis, suicides, and even tripping accidents that will happen when an emaciated prisoner has to carry 50 kg stones up almost 200 uneven steps with no railing day after day.

Boix, who had been a journalistic photographer previously, was assigned to work for a Nazi officer who took pictures in the camp – particularly pictures of fatalities. Boix carried equipment, set up lighting, developed negatives, and made prints. His boss, Ricken, is depicted as bizarre character. On the one hand, Ricken seems not so bad by Nazi SS standards, but, on the other hand, he has a sociopathic inclination to see death as art. Boix takes advantage of his position to make copies of the negatives with the idea that they will be evidence when the war comes to the end. At first, there is support for this plot among the Spanish Communists, who help hide the negatives away in places like the carpentry shop. However, this support dwindles when it becomes clear that the Germans will lose the war, and – thus –surviving to the end becomes everyone’s primary focus. Soon Boix is on his own to figure out how to get the photos out. He develops a plan involving one of the boys at the camp (children being less intensely scrutinized) and an Austrian woman, who is a sympathizer.

The book climaxes with the operation to get the negatives out of the camp, but resolves with the immediate post-War period when Boix attempts to generate interest in the photographs as well providing testimony at the Nuremberg Trials. Boix is portrayed as fiery and impassioned. When the others at Mauthausen just want to survive to the end, he maintains that any risk is worth it. While he is shown to have some conflict about putting a boy’s life at risk with (arguably) the riskiest step in the process, he doesn’t seem waiver. At the trials he’s outraged about the panel’s insistence on “just the facts.” He wants to freely and fully tell the story of Mauthausen, and they – like courts in democracies everywhere – wish to maintain an appearance of the dispassionate acquisition of facts.

I found this book to be engaging and well worth the read. The artwork is well-done and easy to follow. The story is gripping. While there are a vast number of accounts of events at places like Auschwitz, there aren’t so many popular retellings of events at Mauthausen. I highly recommend this book for those interested in events surrounding World War II and the Holocaust.

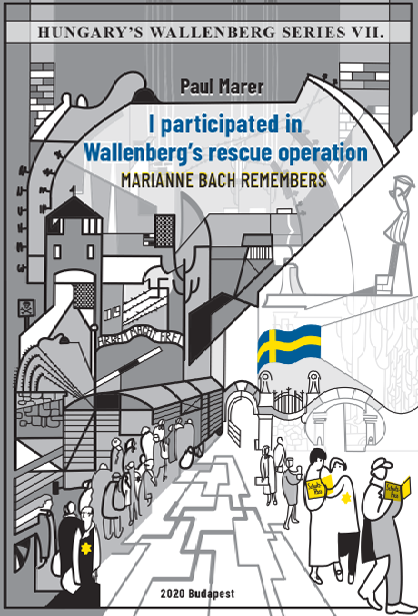

BOOK REVIEW: I Participated in Wallenberg’s Rescue Operation by Paul Marer

I Participated in Wallenberg’s Rescue Operations by Paul Marer

I Participated in Wallenberg’s Rescue Operations by Paul Marer

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Inquiries about purchasing the book can be made here.

In 1944, the Nazis were working to eradicate the European Jews. Among the last major Jewish populations accessible to Hitler that had yet to be shipped to the death camps were those from Budapest. Among the most effective forces arrayed against the Nazis and the Arrow Cross Militia (the Hungarian fascists) in the days before the Red Army arrived were neutral nation diplomats who issued protective documentation, offering at least a thin shield of legal protection that saved thousands of lives.

Perhaps the most intriguing story of such diplomats is that of the Swedish envoy, Raoul Wallenberg – not because his operation was bigger or riskier than those of the others, but because his story didn’t end with the war. Wallenberg was captured by the Soviets at the end of the Siege of Budapest for reasons that remain speculative, and he died in a Soviet prison. This book draws on the experience of Marianne Bach, a young member of Wallenberg’s team. Given the loss of Wallenberg, and the fact that the other members of his operation are now deceased, Bach’s story is an important last chance to learn more detail about what happened in Budapest during those dark days.

The book is chronologically arranged. The first two and the last three chapters discuss Marianne Bach’s life before and after, respectively, her days working as part of Wallenberg’s team. A reader might dismiss such chapters as humdrum, if necessary, background information, and starkly contrast them with the more high-octane, life-and-death, fascist-fighting core of the book. However, Marer fixes his sights on an intriguing focal point throughout these chapters, identity (and crises, thereof.) Both before and after the war, Bach was challenged by questions of identity – religious, cultural, and national identity. Living abroad, she was a foreigner, but at “home” in Hungary there’d been a great effort to eliminate her people. It was smart to focus on events and questions at the crux of identity. It makes these chapters engaging to a degree that a broad biographical sketch would be hard-pressed to achieve.

The core of the book (ch. 3 – 8) doesn’t just tell Bach’s story – in fact, it doesn’t just tell the Wallenberg story, it delves into the broader question of the fate of the Budapest Jews and all those who intervened to save whomever they could. This isn’t to say that the closeup story is absent. Readers get a detailed view of the operations that Bach was involved in and an overview of the Wallenberg story – including discussion of his fate as a secret Soviet prisoner. It’s just that those closeup stories are embedded within a broader context that includes activities like Carl Lutz’s Glass House operation, Hitler’s order to take over of Hungary before it could defect from the Axis, and the Danube executions by Arrow Cross Militiamen that followed that takeover.

This book provides a gripping examination of a disturbing time, and I’d highly recommend it.

BOOK REVIEW: Carl Lutz (1895-1975) by György Vámos

Carl Lutz by György Vámos

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon page (only the French edition is currently showing)

Carl Lutz was a Swiss diplomat assigned to Budapest in 1944, at the time the Nazis and their Arrow Cross comrades were trying to deport the Budapest Jewry to death camps. Lutz may not be as well know as his Swedish counterpart, Raoul Wallenberg, but that’s not for lack of saving lives. Like Wallenberg, he saved thousands of Jews by issuing protective documentation, and by fudging numbers and background documents where necessary to keep more people safe.

Lutz also oversaw a facility where the people issued these documents were allowed to stay to keep them out of the city ghetto from which they might get caught up in deportations. The Swiss-flagged facility was called the “Glass House” because it was on the grounds of a factory where specialty glass had been made, and the building’s façade was covered in multiple styles of glass as a way for perspective customers to see what products were available. Unfortunately, the property wasn’t designed for residential use, let alone for providing facilities for large numbers of people. Quarters were cramped and hygienic facilities were inadequate. However, the facility did keep people alive, even though it was raided by the Arrow Cross. [For those visiting Budapest, a small museum / memorial room can still be found at this same location, and this book’s author can offer more insight.]

The book is written in a scholarly style, i.e. employing a historian’s tone. It largely follows a chronological format. The book doesn’t discuss Lutz’s life much outside the war years, but it does give the reader background about Hungary’s anti-Semitic laws and actions as well as an overview of strategic-level events. [Hungary was allied with Germany in the Second World War, but in 1944 tried to separate itself and stop deportations. This resulted in Germany taking control and handing power to the Arrow Cross Militia, which was the Hungarian fascist party — akin to the German Nazis.]

The book is concise, weighing in at only 125 pages — about 17 of which are in an appendix of documents and photos regarding Swiss efforts to undermine the Nazi’s Holocaust.

As I said, the book is written in a scholarly / historical format, rather than the more visceral narrative approach of a journalistic or popular work. Still, it does become more intense reading in the latter half — when the author is describing events concerning the Glass House, Lutz’s issuance of protective documentation, and the siege of Budapest by the Russians at the end of the war. It will certainly give readers insight into a little-known rescue effort during the Holocaust.

If you’re interested in international efforts to thwart the Nazi’s plan to exterminate the Jews, this book will clue you in on events that aren’t well-known – particularly by English readers. I highly recommend this book.

BOOK REVIEW: The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

One might think that a book narrated by Death and set in Nazi Germany during the Second World War would be bleak from cover to cover. But one would be wrong. “The Book Thief” heaps hope and humor upon the reader, saving tragedy for the final course – besides a few sprinkles throughout. It’s not that the story lacks a tension born of many close calls and morally compromised situations, but it’s a very human story – with the appropriate mix of blemishes and beauty.

The protagonist is a girl named Liesel who is sent to live with foster parents during the first year of World War II. Traveling to meet her new family, her brother dies, leaving her alone with new parents in a new city on the doorstep of the most lethal war in human history. In the cemetery, after her brother’s impromptu funeral, Liesel finds a fallen book and keeps it. It’s the first of several books she will “steal,” acts that will define her but which are comic sins in the shadow of the mass murder in progress. Fortunately, Liesel’s foster parents are salt of the earth folk. They aren’t wealthy or erudite, but they offer Liesel a loving home. It’s a little harder to see this affection in her foster-mother, who has a stern and gruff exterior — in contrast to her papa who is endearingly sympathetic.

The story is about this family, and others in the neighborhood, trying to get through life under a regime they recognize as tragically absurd, but which is terrifying none-the-less. Besides surviving, characters like Liesel’s papa try to do the right thing whenever they can, in whatever way won’t get them killed. Life gets harder as the war wears on. Liesel’s papa is a house painter, an occupation that is not a year-round occupation in Germany. Liesel’s mother does laundry, a luxury that most can’t afford as the war rages. On the other hand, this doesn’t make them worse off than most of the others on Himmel Street, which is – figuratively speaking – on the wrong side of the tracks.

While this is an engaging story, Death as narrator is the feature that really makes this book exceptional to me. Much of the lightness and humor comes from the fact that the narrator is not grim, but rather has humor and a stilted form of humanity about him. From a narrative perspective, Death offers a unique point of view, but it’s the circumvention of expectations that comes from the fact that Death can recognize the tragedy of what is unfolding before him. He’s not emotional about it in the way a human would be, but neither does he ignore the brutality and absurdity of it. The other factor that catapults this book beyond the realm of run-of-mill war story, is how the desire for literature and learning — which would usually be lost in a war story’s struggle for survival – is given a prominent role.

I enjoyed this book immensely. It’s an intensely human story, neither saturated in sorrow nor ignoring the horrors of war and genocide. I highly recommend it for fiction readers.

POEM: A Mile of Murder

On a moonlit midnight —

On a moonlit midnight —

between the bands of rain —

stretched a mile of murder.

Marched through the night

to keep day roads clear for troops,

Fascists sought to free themselves

of the ugly evidence of their crimes.

But sweeping the weary and woebegone

under the rug is not a rapid task,

and so a mile of murder

mass migrated towards the morn.