The Two Noble Kinsmen by William Shakespeare

The Two Noble Kinsmen by William Shakespeare

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in page

King Creon of Thebes is a jerk. The play opens with three Queens petitioning the Duke of Athens, Theseus, to avenge the kingly husbands that Creon had executed. Theseus ultimately agrees. We know that Creon is really a jerk [and not that the Queens are being spoilsports (or duplicitous)] because Creon’s own nephews – Palamon and Arcite, the titular two noble kinsmen – are about to high-tail it out of Thebes to get away from Creon’s reign when they learn Theseus has attacked. These two aren’t the kind to shy away from a fight, and so – instead of leaving – they fight for Thebes, despite its jackwagon of a King. The two fight with valor, but are no match for Theseus’s forces and are captured, becoming prisoners of Athens.

Palamon and Arcite are paragons of manliness, the kind of men who other men want to be and that ladies want to be with. They are handsome, virtuous, athletic, and likeable. The two share a bond that one might think unbreakable, until the beautiful Emilia enters the picture. Through the window of the jail, Palamon spots Emilia in the garden and is stricken by love at first sight. When Arcite says he, too, has the hots for Emilia (who they both only know by sight and from a distance,) Palamon is suddenly ready to kill his kinsman and brother in arms. Palamon is over-the-top in his anger, especially as it seems unlikely at that moment that either of them is likely to meet Emilia. [I suspect Arcite really likes Emilia, too, but one can’t eliminate the possibility that the elaborate antics to follow are all for the principle of the matter because Palamon is so insistent that Arcite has no right to pursue Emilia. As if Palamon had called “shotgun” and Arcite had tried to jump up front.]

However, soon Arcite is summoned to the palace, and he ends up being banished from Athens. He’s told that he doesn’t have to go home, but he can’t stay in Athens. Arcite starts to head back to Thebes, but then he finds out that Athens is having a field day (by that I mean a day of sports and competition, not in the colloquial sense of the word) he decides to disguise himself and compete in the hopes of winning Emilia’s heart (and / or getting Palamon’s goat.) (Winning Emilia is no small feat given Emilia’s high standards and – given her adoring talk of her relationship with a friend named Flavina – a likely lesbian inclination.) But we’ve established that Arcite is a man among men, and he trounces the competition, and – in doing so — does get to meet Emilia.

Meanwhile, back in the jail, Palamon is no slouch himself. By way of a combination of charisma and machismo, the jailer’s daughter has fallen as fast and stupid for him as he did for Emilia. The daughter ends up breaking Palamon out of jail. Shortly after that, the she goes coo-coo for coco puffs insane when she realizes: a.) being a commoner, Palamon could never fall for her, and b.) in all probability her father will be hanged when Theseus realizes Palamon is no longer in the prison, and her father’s blood will be on her hands.

Palamon and Arcite meet. Palamon has not cooled down, and is more ready than ever to kill his kinsman — but in a duel, because he’s a gentleman, not a heathen. Arcite provides food and medicine, and tells Palamon he’ll back in a week with two swords and two suits of armor so they can hold their deathmatch in a style befitting gentlemen. I don’t know how much it was intended, but the absurdist humor of these two men alternatingly assisting and threatening to gut one another is hilarious. One could build a Monty Python sketch on it with some tweaking and exaggeration.

Palamon is good to his word, and (after helping each other on with the other’s armor) the two commence their duel, but are interrupted by a deus ex machina hunting trip featuring Theseus, Hippolyta (his wife), Emilia, and Pirithous (a gentleman friend of Theseus’s.) Theseus is angry and is ready to have the two men hauled off for execution. The kinsmen genteelly request that they be allowed to finish out the duel so that one of them will die a little ahead of the other by the other’s hand. Theseus denies this request, but everyone loves these dudes (even Pirithous seems to have a bro-crush on them) and they all intercede.

Theseus has a change of heart. He offers Emilia the option of picking which one she’ll marry, and the other will be executed. Emilia says thanks for the offer of god-like powers, but that she’ll pass. She says she’ll marry whichever one comes out alive, but she’s not going to be judge, jury, and executioner. Then Theseus tells the two kinsmen to leave for one month, during which time they are to be civil to each other. When they come back, they’ll bring three knights with them. (BTW, bad deal for the knights who also die if their boy doesn’t win the competition, but they are all knightly stoic about it.) Then they’ll have a competition in which whichever man can force the other man to touch a pillar will win Emilia’s hand and the other one will be executed.

I’ll leave the reader to read how it plays out. I believe I read that this play was called a comedy on its playbill, but its one of the plays that there is no consensus in categorizing. Unlike “Macbeth,” which is always called a tragedy, or “Taming of the Shrew” which is uniformly labeled comedy, there is significant difference of opinion on this one.

All the while the two noble kinsmen’s stories are playing out, a subplot is afoot in which the jailer’s daughter has gone mad, and efforts are being made to snap her out of it. It turns out that her father, the jailer, was not in danger because Palamon didn’t rat her out, and probably because Theseus assumed Palamon burned through the locks with a smoldering look.

This is a straightforward and entertaining tale. Yes, it has its share of deus ex machina happenings (the fortuitous fox hunt is neither the first nor last), but that’s the nature of theater. Furthermore, I found parts of it hilarious, particularly when the kinsmen are getting armored up for their duel.

This was amongst Shakespeare’s final plays, and it’s said that he had a co-author on it. So, it’s got a little bit different feel. It’s not categorized as a problem play, but as I mentioned some call it a comedy and others a tragedy. Either way, you should definitely read it.

View all my reviews

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

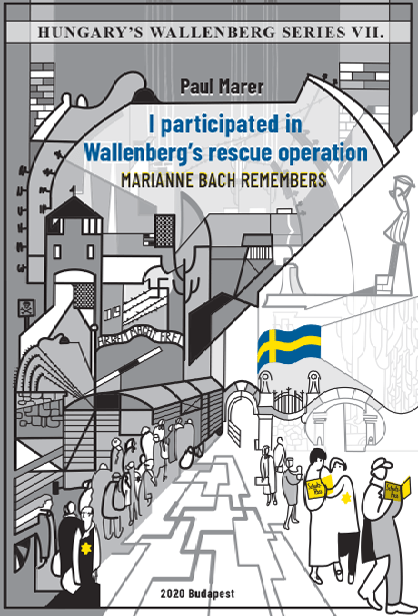

I Participated in Wallenberg’s Rescue Operations by Paul Marer

I Participated in Wallenberg’s Rescue Operations by Paul Marer