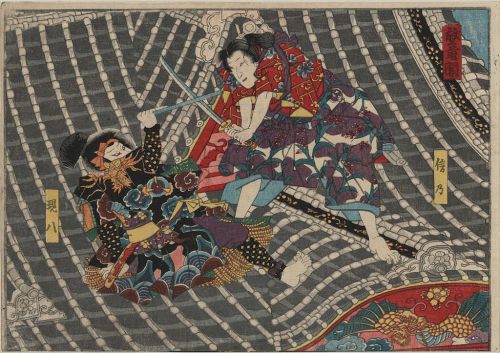

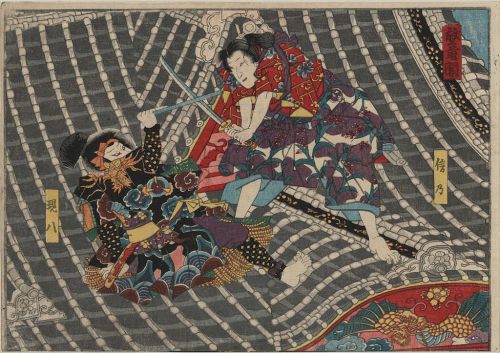

Imagine you’re a detective in Edo Period Japan (1603-1868), and you’re told to investigate a case in which three highly-trained practitioners of one of the most well-respected jujutsu schools have been stabbed to death. Each of the three bodies has only one mark on it–the lethal stab wound. The wound is on the right side of the abdomen in all three cases. There are no signs of a prolonged struggle, despite the fact that each of the three had many years of training and none of the men was an easy victim. The stabbings happened independently, and there were no witnesses to any of the killings. So, who or what killed these three experts in jujutsu?

Nobody knows who killed them, but a rigid approach to training contributed to what killed them. As you may have guessed, the killer took advantage of knowledge of the school’s techniques, i.e. their “go-to” defense / counter-attack for a given attack. It’s believed that the attacker held his scabbard overhead in his right hand, and his weapon point forward in a subdued manner in his left. All three of the defenders must have instinctively responded to the feigned downward attack as the killer stabbed upward from below with the unseen blade.

It’s a true story. I read this account first in Jeffrey Mann’s When Buddhists Attack. That book offers insight into the question of what drew some of the world’s deadliest warriors (specifically, Japan’s samurai) to one of the world’s most pacifistic religions (i.e. Buddhism–specifically Zen Buddhism.) Mann cites Trevor Leggett’s Zen and the Ways as the source of the story, and Leggett’s account is slightly more detailed.

This story intrigues because it turns the usual cautionary tale on its head. Normally, the moral of the story would be: “drill, drill, drill…”

Allow me to drop some brain science. First, there’s no time for the conscious mind to react to a surprise attack. The conscious mind may later believe it was instrumental, but that’s because it put together what happened after the fact and was ignorant of the subconscious actors involved. (If you’re interested in the science of the conscious mind’s stealing credit ex post facto [like a thieving co-worker], I refer you to David Eagleman’s Incognito.) Second, our evolutionary hardwired response to surprise is extremely swift, but lacks the sophistication to deal with something as challenging as a premeditated attack by a scheming human. Our “fight or flight” mechanism (more properly, the “freeze, flight, fight, or fright” mechanism) can be outsmarted because it was designed to help us survive encounters with predatory animals who were themselves operating at an instinctual level. (If you’re interested in the science of how our fearful reactions sometimes lead us astray when we have to deal with more complex modern-day threats, I refer you to Jeff Wise’s Extreme Fear. Incidentally, if you’re like, “Dude, I don’t have time to read all these books about science and the martial arts, I just need one book on science as it pertains to martial arts,” I just so happen to be writing said book… but you’ll have to wait for it.)

So where do the two points of the preceding paragraph leave one? They leave one with the traditional advice to train responses to a range of attacks into one’s body through intense repetition. Drill defenses and attacks over and over again until the action is habitual. This is what most martial artists spend most of their training effort doing. A martial art gives one a set of pre-established attacks or defenses, and it facilitates drilling them into one’s nervous system.

Of course, the astute reader will point out that the three jujutsu practitioners who were killed had done just what was suggested in the preceding paragraph, and not only didn’t it help them but–arguably–it got them killed. I should first point out that the story of the three murder victims shouldn’t be taken as a warning against drilling the fundamentals. As far as their training went, it served them well. However, there’s a benefit to going beyond the kata approach to martial arts. One would like to be able to achieve a state of mind that once would have been called Zen mind, but–in keeping with our theme of modern science–we’ll call transient hypo-frontality, or just “the flow.” This state of mind is associated with heightened creativity at the speed of instinct. (If you’re interested in the science of how extreme athletes have used the flow to make great breakthroughs in their sports, I’d highly recommend Steven Kotler’s The Rise of Superman.) Practicing kata won’t help you in this domain, but I believe randori (free-form or sparring practice) can–if the approach is right.

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.