You Only Live Twice by Ian Fleming

You Only Live Twice by Ian Fleming

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

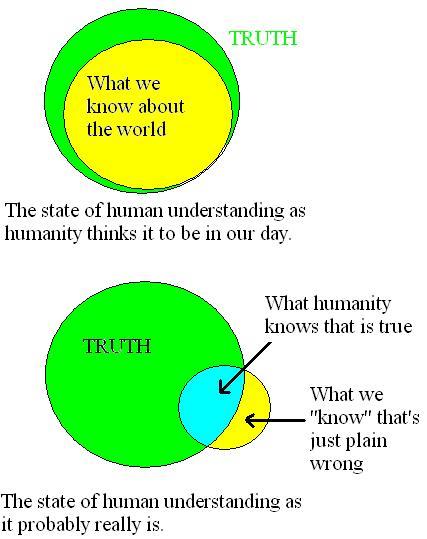

When the film Casino Royale came out, it was panned by Roger Ebert, but not because it was a bad film. What Ebert didn’t like about that movie was that it looked and felt a lot more like the lead should have been named Jason Bourne rather than James Bond. In other words, Daniel Craig portrayed the super-suave secret agent with a license-to-kill as a gritty brawler and not the superman who could take on a swarm of SPECTRE henchmen without getting dust on the labels of his impeccable Armani. The latter is the archetypal James Bond.

The problem for film-makers is that the old Bond hasn’t aged well and seems a more suitable basis for Austin Powers’ style parodies than gripping thrillers.

You Only Live Twice is an entertaining read, but it’s best described as delightfully campy. However, it wasn’t meant to be camp when it came out. That being said, the film–which bears only a superficial resemblance to the novel–made changes specifically to make the storyline make more sense (that’s an odd twist for Hollywood.)Specifically, the arch-villain’s motivation doesn’t seem to make much sense in the novel. We are supposed to accept that the fact that the man is mad and evil to the core is sufficient for him to do something randomly quasi-evil, even if it offers him no benefit.

The synopsis is as follows: At the beginning, we find James Bond in turmoil. His wife died in the last book (within 24 hours of their marriage), and Bond has taken it hard. Since then he’s botched a couple of missions. He’s called into M’s office and thinks he is about to be canned. (He’s almost right.) Instead, M sends him on an assignment to Japan. It’s a challenging mission, but–theoretically–one of a diplomatic nature. Bond is to get Japan to turn over information from a code breaking technology they’ve developed. The Japanese only give this information to the U.S., and America is spotty at passing on relevant information to Britain.

Bond strikes up a friendship with “Tiger” Tanaka, who has no use for the bargaining chip which Bond has to offer. However, Tanaka agrees to hand over the information if Bond will take care of a delicate situation for Japan. In the country’s remote south, a European has set up a “toxic garden” of poisonous plants, animals, and insects. This garden has become a Venus flytrap for (the apparently infinite waves of)suicidal Japanese people.

Bond agrees to the proposal, and latter finds out that the European horticulturist is actually none other than the arch-nemesis who killed his wife, one Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Bond spends a couple of days in a fishing village reconnoitering and establishing the book’s romantic interest in the form of Kissy Suzuki–a pearl diver who was for a brief time a Hollywood starlet.

Bond makes his ninja-like infiltration of the Blofeld castle. I won’t get into how the climax of the book unfolds, but needless to say our hero wins the day.

The most thought-provoking part of the book may just be what happens after Bond finishes his mission. At the mission’s end, he develops amnesia as a result of a head injury. This amnesia makes the book’s title apropos.

There are some interesting themes addressed in the book. For example, there is considerable discussion of the difference of perspective on suicide between the West and Japan. Japan retains some of the samurai era notion that suicide can be used to restore honor, while Bond defends the Western view that suicide is a cowardly out. Still, while the Japanese attitude toward killing oneself when added to the stresses of a Japanese lifestyle (e.g. salaryman living) has resulted in a somewhat heightened suicide rate, the issue is greatly exaggerated to make the premise of Blofeld’s “Death Garden” seem remotely credible.

There’s also a great deal of discussion of Britain’s decline and America’s rise. Great emphasis is put on the fact that the Pacific is “America’s domain” and that the Brits have to be sneaky to operate there–lest they be at the mercy of their former colony.

This novel (and its film) introduced many exotic elements of Japanese culture to an audience beyond the Japanophiles for whom they were no surprise. This exotica includes ninja (spies of medieval Japan), fugu (poison blowfish–a potentially lethal delicacy), and Geisha (female entertainers and escorts.) It’s clear Fleming put some research into these matters. However, it also seems like he picks every element of Japanese history and culture that Westerners would find odd and unusual. At some points, one wonders what stereotype Fleming will next exploit.

There are a lot of patently ridiculous happenings in the book. At one point while Bond is hiding out on the grounds of the garden in a manner reminiscent of the ninja of old, biding his time, he decides that he simply must have a cigarette. Now, I’m not going to get into the plausibility of someone with that bad of an addiction having been able to swim a mile through waters with treacherous currents after having spent a few days rowing out to pearl dive. However, the notion that a special operative would light up in the middle of a covert operation is pretty far-fetched. It’s like saying, “I don’t care if this mission succeeds or even if you kill me, I’m going to have my Marlboro moment.” Some readers may think I’m engaging in hyperbole, but not those of you who’ve been in the military. The scent of cigarette smoke is extremely potent, and then there’s the glow. You don’t get out of boot camp without learning that you don’t smoke on LP/OP (Listening Post / Observation Post,) let alone into Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Bond’s transformation through makeup into a person who looks passably Japanese is another point at which credulity is strained. This make up survives ocean swims, fights, and even after the mission when Bond has amnesia, he can’t recognize that he, himself, looks nothing like the villagers of his hometown hamlet. (Tiger Tanaka has a card printed that says that Bond is deaf and dumb to get around his inability to speak the local language. [Props to Fleming for not going the Hollywood route and making his spy fluent in every imaginable language.])

The most ridiculous piece of the book involves an elaborate machine works that Blofeld uses to make the volcano let off liquid hot magma every 15 minutes like clockwork. He has this ready in anticipation of a need to test whether a victim can understand his instructions to get up and walk out to avoid being burned with hot lava. If Bond understands, he must not be deaf and dumb like the card says, and if he stays put–oh, well, he’s just a deaf and dumb coal miner who went sleepwalking in his ninja suit and ended up inside the heavily guarded castle retreat of the SPECTRE leader. What’s more, he puts the control for this Rube Goldberg contraption where the interrogated can see it (a fact that Bond later puts to use), and even though it’s inside a box, Bond knows exactly what it must be (he’s just that good.)

And, of course, in the most mocked device in this genre, Blofeld gives a long speech when he should be killing Bond.

You’ve got to read this with a certain mindset, and if you want a realistic, gritty thriller you’re not in the right mindset.

As I said, the movie doesn’t have a whole lot to do with the book besides borrowing some character names and a few scenes. However, below is the trailer for the movie.