Handbooks for Daoist Practice: Scriptural Statutes of Lord Lao by Louis Komjathy

Handbooks for Daoist Practice: Scriptural Statutes of Lord Lao by Louis KomjathyMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Author Site

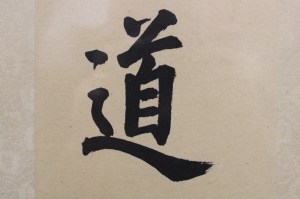

This paper presents exposition on, and translation of, an important Taoist work. Like many collections of sutras and other epigrams of wisdom, the “Scriptural Statutes of Lord Lao” are only a couple pages of sayings. To be more specific, they consist of nine practices (九行) and twenty-seven moral precepts. The bulk of the twenty-five-ish pages of this work are a scholarly background on the nine practices and twenty-seven precepts, plus back matter including references and the original (Chinese) “statutes.”

I read this because the nine practices seem like a concise statement of what it means to be Taoist (a topic that can be tremendously complicated given the varied sects, beliefs, and practices that all fall under the heading of “Taoist” — some religious, some philosophical, and some mystical.) Those nine practices are: non-action (which is much more complicated than just sitting on one’s bum,) softness, guarding the feminine, namelessness, stillness, adeptness, desirelessness, contentment, and knowing how and when to yield. The text offers some insight into where these practices come from (e.g. the points in the Dao De Jing that reverence them,) but the scope of the work is far to limited to gain a deep understanding of them (for that one will have to go elsewhere.)

I found reading this short work to be quite beneficial and insightful, despite its thin profile. I’m glad it includes the original text as well as provides citations, as therein much of its value lies.

View all my reviews