A narrow Fellow in the Grass

Occasionally rides --

You may have met him? Did you not

His notice instant is --

The Grass divides as with a Comb,

A spotted Shaft is seen,

And then it closes at your Feet

And opens further on --

He likes a Boggy Acre --

A Floor too cool for Corn --

But when a Boy and Barefoot

I more than once at Noon

Have passed I thought a Whip Lash

Unbraiding in the Sun

When stooping to secure it

It wrinkled And was gone --

Several of Nature's People

I know, and they know me

I feel for them a transport

Of Cordiality

But never met this Fellow

Attended or alone

Without at tighter Breathing

And Zero at the Bone.

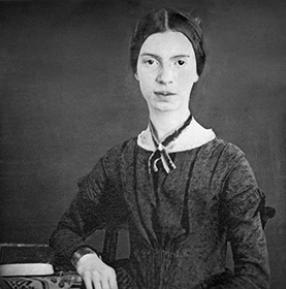

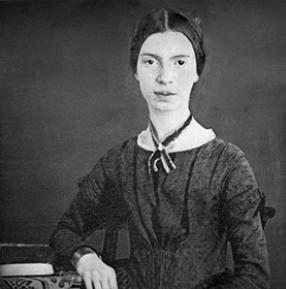

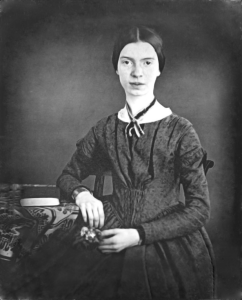

Tag Archives: Emily Dickinson

“There is no Frigate like a Book” (1286) by Emily Dickinson [w/ Audio]

Tell all the truth but tell it slant — (1263) by Emily Dickinson [w/ Audio]

I dwell in Possibility (466) by Emily Dickinson [w/ Audio]

I dwell in Possibility -- A fairer House than Prose -- More numerous of Windows -- Superior -- for doors -- Of Chambers as the Cedars -- Impregnable of eye -- And for an everlasting Roof The Gambrels of the Sky -- Of Visitors -- the fairest -- For Occupation -- This -- The spreading wide of my narrow Hands To gather Paradise --

BOOK REVIEW: American Poetry: A Very Short Introduction by David Caplan

American Poetry: A Very Short Introduction by David Caplan

American Poetry: A Very Short Introduction by David CaplanMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

Get Speechify to make any book an audiobook

This book does a great job of helping the reader understand what distinguishes the American strain of poetry from other poetic traditions, particularly the one from which it sprang and to which it’s most closely related, linguistically speaking: i.e. English poetry. Among the unique aspects of American poetry are a shift toward more idiosyncratic poetry, a shift that flows from America’s individual-centric orientation, the employment of American idiom – especially informal language, the connection to other American artforms (e.g. Blues music,) the diversity of form and style that resulted from being a diverse population, and the loud and clear expression of dissenting voices.

The page limitations of a concise guide keep this book from drifting wide in its discussion. The reader will note that it’s focused on mainstream poetry, and there’s little to no mention of counter-cultural movements, e.g. the Beats (e.g. Ginsberg and Synder) are not discussed. However, even within the restriction to mainstream poets, there’re only a few poets that are discussed in depth. Of course, these include the two poets largely considered the pillars of the American form: Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. It also includes two poets who were challenging cases for a discussion of national poetic movements: W.H. Auden, a Brit by birth who spent most of his poetry writing years in America; and T.S. Eliot, who was an American by birth but moved to Britain. Both poets produced poetry of importance while on both sides of the Atlantic, and, so, the question is whether anything of note can be said about their poetry vis-a-vis its location of origin (and, if not, have we exited the era in which nationality of poetry is worth discussing?)

I learned a great deal from this book. Again, if you’re looking for a broad accounting of American poetry, this isn’t necessarily the book for you, but if you want to gain a glimpse of the interesting and unique elements of American poetry through a few of its most crucial poets, this is an excellent choice.

View all my reviews

Clerihew of American Literary Greats

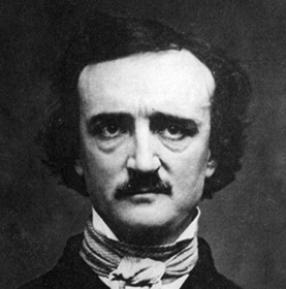

I

Edgar Allan Poe

always lacked for dough.

Still, he always strived

to not be buried alive.

II

Emily Dickinson

lived a bit like a nun,

but her verse was insightful —

even sans an earthly eyeful.

III

Samuel Clemens, or Mark Twain,

wrote personas known to speak plain.

His nom de plume

means “fathoms, two!”

IV

The poet Walt Whitman

had a startled milkman.

Never one to be subdued,

if you just dropped by, he might be nude

POEM: _____________________ [Day 29 NaPoMo: Dickinsonian]

[Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman were poetic revolutionaries whose new approaches to the art were highly influential in the creation of a distinctive American tradition of poetry. It’s often said that all Dickinson’s poems are written in common meter (alternating lines of four and three feet) and can thus be sung to “Yellow Rose of Texas” or “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” While that’s not perfectly accurate, it is true that a substantial portion of her work fits that mold. In terms of form, the other thing Dickinson is famed for is the use of dashes, though there is no consensus agreement about a well-defined rationale for their use.

Moving from form to content, Dickinson’s style offers a singular approach to metaphor. Also, while she usually deals in weighty topics such as death and loneliness, her verse often has a whimsical / witty tone. (e.g. “Because I could not stop for Death — He kindly stopped for me –” (479)) Her poems normally feature a first person and frame that person as — first and foremost — an observer (i.e. a seer and a hearer.)

Also, I’ve not put a title to this poem because Dickinson didn’t title her poems. They are normally ordered by first line, a number, or both. This isn’t a form of laziness, but seems to reflect Dickinson’s preference for propelling the reader into the heart of the matter without prelude.]

A Poem lands a heavy blow

against these muted walls.

To those who think this Cell, my cell —

I’m never here — at all.

For I’m a wave on churning Seas —

a thousand miles away.

‘Twas written so — long days ago,

no page has bid me stay.

5 Posthumous Gods of Literature; and, How to Become One

There have been many poets and authors who — for various reasons — never attracted a fandom while alive, but who came to be considered among the greats of literature in death. Here are a few examples whose stories I find particularly intriguing.

5.) William Blake: Blake sold fewer than 30 copies of his poetic masterpiece Songs of Innocence and Experience while alive. He was known to rub people the wrong way and didn’t fit in to society well. He was widely considered insane, but at a minimum he was not much for falling in with societal norms. (He probably was insane, but cutting against the grain of societal expectations has historically often been mistaken for insanity.) While he was a religious man (mystically inclined,) he’s also said to have been an early proponent of the free love movement. His views, which today might be called progressive, probably didn’t help him gain a following.

4.) Mikhail Bulgakov: Not only was Bulgakov’s brilliant novel, The Master & Margarita, banned during his lifetime, he had a number of his plays banned as well. What I found most intriguing about his story is that the ballsy author personally wrote Stalin and asked the dictator to allow him emigrate since the Soviet Union couldn’t find use for him as a writer. And he lived to tell about it (though he didn’t leave but did get a small job writing for a little theater.) Clearly, Stalin was a fan — even though the ruler wouldn’t let Bulgakov’s best work see the light of day.

3.) John Kennedy Toole: After accumulating rejections for his hilarious (and posthumously Pulitzer Prize-winning) novel, A Confederacy of Dunces, Toole committed suicide. After his death, Toole’s mother shopped the draft around and brow-beat Walker Percy into reading it, which ultimately resulted in it being published.

2.) Emily Dickinson: Fewer than 12 of Dickinson’s 1800+ poems were published during her lifetime. Dickinson is the quintessential hermitic artist. Not only wasn’t she out publicizing her work, she didn’t particularly care to see those who came to visit her.

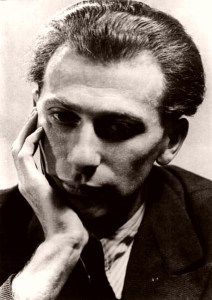

1.) Franz Kafka: Kafka left his unpublished novels The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika, as well as other works in a trunk, and told his good friend Max Brod to burn it all. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending upon your definition of a good friend), Brod ignored the instruction and the works were posthumously published.

In brief summary, here are the five ways to become a posthumous god of literature:

5.) Be seen as a lunatic / weirdo.

4.) Live under an authoritarian regime.

3.) Handle rejection poorly, lack patience, and / or fail to get help.

2.) Don’t go outside.

1.) Wink at the end of the sentence when you tell your best friend to burn all your work.

POEM: You’re Killing Me, Ms. Dickinson, or: Samurai Surgery

“If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” – Emily Dickinson

It’s mean accuracy and angry power that can cleave the top off a head;

neither merely scalping the reader,

nor decapitating him.

Popping the top to blow the mind is samurai surgery.

Some lines tink against the forehead like a dull knife,

while others — with razor-sharpness — succeed only in shearing an unsightly bald spot.

The fabled Taoist butcher could cleanly slice between the bone ends,

never dulling his cleaver,

but that’s not much help for one seeking to take off the top of a head…

or is it?