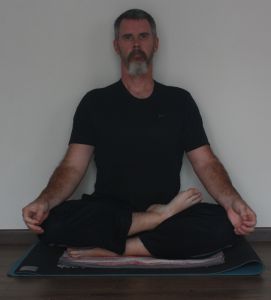

Sukhasana (Easy Pose)

5.) Sukhasana (Easy Pose): One simply folds the legs so that each leg rests on top of the opposite foot. This is a popular crossed legged seated posture. For reasons to be explained, it’s usually not considered a meditative posture.

Pros: As the name suggests, it’s an easy seat for most people to assume. Because the leg is resting on the opposite foot, the knees don’t have to (re: can’t) lay flat on the floor, and so this is pose is more comfortable for practitioners with tight glutes or who otherwise can’t open their hips — for short time periods at least.

Cons: The downside of not putting the knees down, is that the posture is not nearly so stable as the others that will be mentioned. Instead of a big triangle running from one’s sit-bones out to the knees and between each knee, one is resting on a small triangle with the gap between the sit-bones as its base. Furthermore, there will be a pronounced tendency to slump in the back in this pose, and this makes Sukhasana not ideal for sitting more than a few minutes.

Notes: As I mentioned, this isn’t a good meditative posture because it’s unstable and prone to back pain over relatively short periods. I mention it here because many beginners can only manage to do this pose. If that is the case for you, you will probably want to look at using props to achieve a comfortable position (e.g. lifting the hips), if you intend to practice more than five minutes or so.

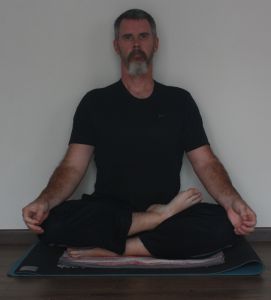

Swastikasana (Auspicious Pose)

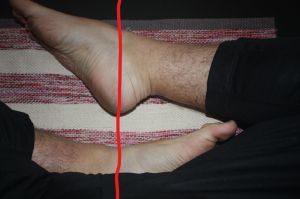

4.) Swastikasana (Auspicious Pose): Note: this pose and the next (Siddhasana – Accomplished Pose) are quite similar, and it’s hard to see the difference in photos, but I’ve added a couple pictures and some text description to try to clarify the difference. Bend the left knee and place the left sole against the inside of the right thigh. One will then bend the right leg and, squeezing the left foot into the space at the crook of the right leg, tuck the right foot into the space between the left thigh and calf muscle. Tucking the feet in is important to making the posture comfortable — particularly the bottom one, which can be compressed if not positioned properly.

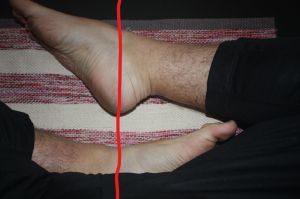

The difference between this pose and Siddhasana is simply that the heels aren’t aligned on one’s center-line, but rather the left heel will be to the right side of one’s center-line and the right heel will be to the left. If one’ imagines the line below were straight and on the body’s center-line, one can see how Swastikasana has the heels / ankles offset.

Pros: The posture is much more stable than Sukhasana and, while not quite as wide a the base as Siddhasana, it avoids Siddhasana‘s disruption of circulation caused by the bottom heel being pressed against the perineum / genitals (depending upon gender.) That makes Swastikasana‘s strength its position on the middle ground. It’s stable enough for meditation but doesn’t require as much flexibility in externally rotating the thighs as does Padmasana (Lotus Pose.)

Cons: Some people (including the author) have troubles squeezing the feet into the gaps between thigh and calf — i.e. if one has thick legs, it can be problematic. Both this pose and Siddhasana are contra-indicated for those with sciatica or sacral infection (Sacroiliitis.) Some traditionalists would say that the lack of stimulation to the moola bandha / perineum is a con as well.

Notes: Both this posture and Siddhasana can be practiced with either leg folded first, and many teachers recommend alternating for those students who spend a lot of time in meditative poses, because the postures aren’t symmetrical and muscular asymmetries may develop if one always does it on the same side.

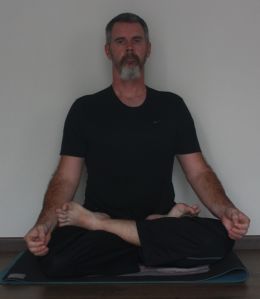

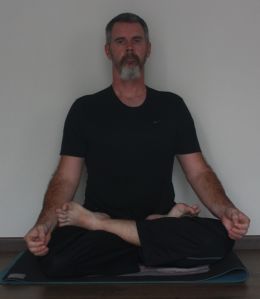

Siddhasana (Accomplished Pose)

3.) Siddhasana (Accomplished Pose): As mentioned, the gist of this pose is the same as Swastikasana, except that the bottom heel will be aligned on one’s center-line, pressing into the perineum lightly, and the heel of the top foot will be in alignment with the bottom foot. (Note: Males will probably have to do some genital re-positioning to make this position comfortable.)

The picture below shows how the heels are aligned on the body’s center-line.

Pros: While not without controversy, many teachers propose that having the heel pressing into one’s body has advantages in stimulating the moola bandha – including helping the practitioner be chaste.

Pros: While not without controversy, many teachers propose that having the heel pressing into one’s body has advantages in stimulating the moola bandha – including helping the practitioner be chaste.

Cons: The aforementioned controversy involves potential damage done by long-term disruption of blood flow in the area. It should be pointed out that there’s no reason to think that short term pressing of the heel into the groin — as is done in janu shirshasana (head-to-knee pose) — is problematic. However, meditation may involve much longer disruption in blood flow. So while some opponents of Siddhasana would agree that it helps attain chastity, they might argue that potentially causing impotence is not an ideal way to achieve that control over one’s sexuality — if control is even needed in the first place.

Note: When practiced by women, this posture is sometimes referred to as Siddha Yoni Asana, which just reflects that contact point with the heel is a bit different owing to differences in anatomy in the region.

Ardha Padmasana (Half Lotus Pose)

2.) Ardha Padmasana (Half Lotus Pose): The left foot will be folded in so that the left sole rests on the right inner thigh, much as in Swastikasana, and the right foot will be folded up into one’s left hip crease with the left heel as close to the navel as possible. One may need a prop (e.g. block or rolled up towel) under one’s elevated knee — especially for long term sitting. As mentioned with regards the previous two poses, this pose can be practiced on either side, giving one the opportunity to work out the asymmetries.

Pros: Half lotus offers some of Padmasana‘s (Lotus Pose) advantage in terms of stability in the lower back, without having to have quite as much flexibility in external rotation of the thigh. As a person with thick legs, but flexible hips, I find ardha padmasana and padmasana tend to be more comfortable than the preceding poses for me, personally.

Cons: The asymmetry of this pose is considerable, and failure to balance it out will be problematic. Also, if one doesn’t have sufficient hip flexibility, one may end up putting a dangerous torque onto the knee joint.

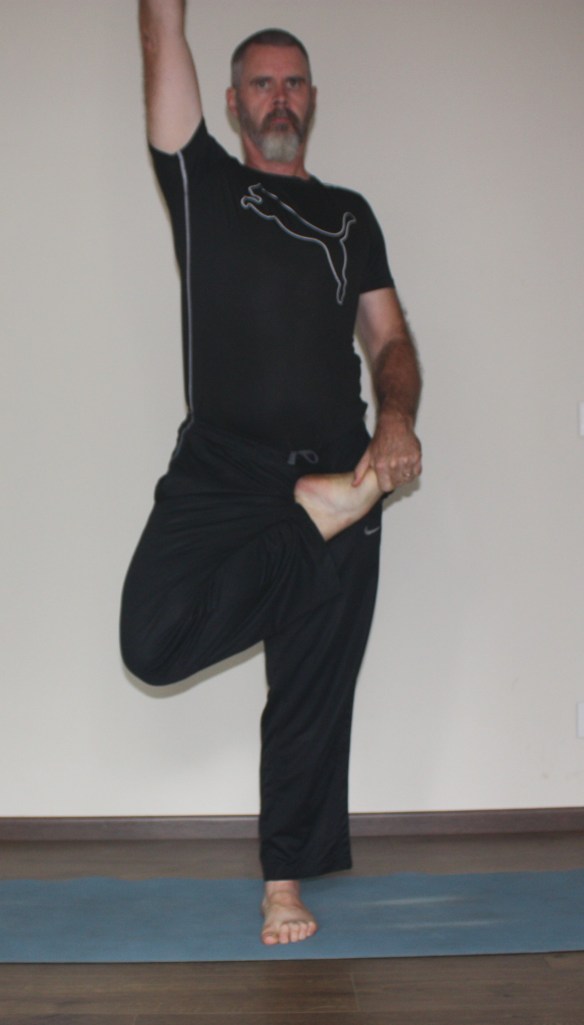

Padmasana (Lotus Pose)

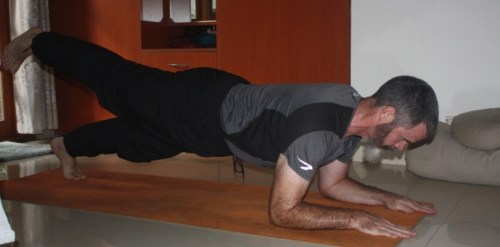

1.) Padmasana (Lotus Pose): One will take the left leg and fold it so as to put the left foot into the crease of one’s right hip with the left heel as close to the navel as possible. One will then take the right foot and folding it over the top of the left so that it comes to rest at one’s left hip crease. One may want to (or need to) press both knees inward to get the legs into a stable position.

Pros: This posture is not only very stable; the lower back achieves a tension that allows one to keep one’s back upright for much longer periods of time without the back starting to slump — leading to the back pain inherent in that slump.

Cons: This takes: a.) a fairly high level of hip flexibility; b.) strong knees that will not become damaged by the torque of getting into or maintaining the pose; c.) the ability to live with discomfort, because it will be somewhat uncomfortable at first even if one has flexible hips and strong knees.

Note: For meditations of less than 30 – 40 minutes, I find padmasana to be the most comfortable and stable pose. However — at least with my thick legs — disruption of circulation of both blood and lymph becomes problematic for longer practices, and in longer meditations I tend to use poses with hips elevated and legs loosely crossed.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of seated poses used in meditation. Notably, there is the posture vajrasana (thunderbolt pose), in which one is seated back on one’s heels with the knees pointing in front of one. Since this pose puts the entire body weight onto the lower legs, circulation disruption can be substantial over long periods. Virasana is similar, but one sits down between the feet, which is challenging for the knees. While both of these postures may be hard to hold in their classic form for extended periods of meditation, variations using props — e.g. a bolster — may be the perfect solution for students who have trouble with all of the poses listed above.

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

Rocket® Yoga: Your Guide to Progressive Ashtanga Vinyasa by David Kyle

Rocket® Yoga: Your Guide to Progressive Ashtanga Vinyasa by David Kyle