I knew a man, a common farmer, the father

of five sons,

And in them the fathers of sons, and in

them the fathers of sons.

This man was of wonderful vigor, calmness,

beauty of person,

The shape of his head, the pale yellow and

white of his hair and beard, the

immeasurable meaning of his black eyes,

the richness and breadth of his manners,

These I used to go and visit him to see, he

was wise also,

He was six feet tall, he was over eighty years

old, his sons were massive, clean,

bearded, tan-faced, handsome,

They and his daughters loved him, all who

saw him loved him,

They did not love him by allowance, they

loved him with personal love,

He drank water only, the blood show'd like

scarlet through the clear-brown skin of

his face,

He was a frequent gunner and fisher, he

sail'd his boat himself, he had a fine one

presented to him by a ship-joiner, he had

fowling-pieces presented to him by men

that loved him,

When he went with his five sons and many

grand-sons to hunt or fish, you would

pick him out as the most beautiful and

vigorous of the gang,

You would wish long and long to be with

him, you would wish to sit by him in the

boat that you and he might touch each

other.

Tag Archives: Leaves of Grass

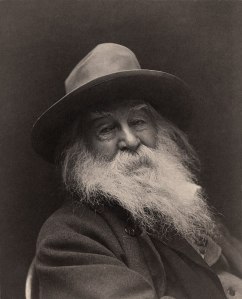

“I Sing the Body Electric” [2 of 9] by Walt Whitman [w/ Audio]

The love of the body of man or woman

balks account, the body itself balks,

account,

That of the male is perfect, and that of

the female is perfect.

The expression of the face balks account,

But the expression of a well-made man

appears not only in his face,

It is in his limbs and joints also, it is

curiously in the joints of his hips and

wrists,

It is in his walk, the carriage of his neck, the

flex of his waist and knees, dress does not

hide him,

The strong sweet quality he has strikes

through the cotton and broadcloth,

To see him pass conveys as much as the best

poem, perhaps more,

You linger to see his back, and the back of

his neck and shoulder-side.

The sprawl and fulness of babes, the bosoms

and heads of women, the folds of their

dress, their style as we pass in the street,

the contour of their shape downwards,

The swimmer naked in the swimming-bath,

seen as he swims through the transparent

green-shine, or lies with his face up and

rolls silently to and fro in the heave of the

water,

The bending forward and backward of

rowers in row-boats, the horseman in his

saddle,

Girls, mothers, house-keepers, in all their

performances,

The group of laborers seated at noon-time

with their open dinner-kettles, and their

wives waiting,

The female soothing a child, the farmer's

daughter in the garden or cow-yard,

The young fellow hoeing corn, the sleigh-

driver driving his six horses through the

crowd,

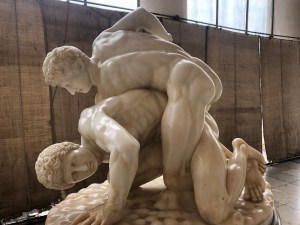

The wrestle of wrestlers, two apprentice-

boys, quite grown, lusty, good-natured,

native-born, out on the vacant lot at sun-

down after work,

The coats and caps thrown down, the

embrace of love and resistance,

The upper-hold and the under-hold, the hair

rumpled over and blinding their eyes;

The march of firemen in their own

costumes, the play of masculine muscle

through clean-setting trowsers and waist-

straps,

The slow return from the fire, the pause

when the bell strikes suddenly again, and

the listening on the alert,

The natural, perfect, varied attitudes, the

bent head, the curv'd neck and the

counting;

Such-like I love -- I loosen myself, pass

freely, am at the mother's breast with the

little child,

Swim with the swimmers, wrestle with

wrestlers, march in line with the firemen,

and pause, listen, count.

“I Sing the Body Electric” [1 of 9] by Walt Whitman [w/ Audio]

I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me

and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them,

respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full

with the charge of the soul.

Was it doubted that those who corrupt

their own bodies conceal themselves?

And if those who defile the living are as bad

as they who defile the dead?

And if the body does not do fully

as much as the soul?

And if the body were not the soul,

what is the soul?

“Gliding O’er All” by Walt Whitman [w/ Audio]

Five Wise Lines from Leaves of Grass

Why, who makes much of a miracle? As to me I know of nothing else but miracles.

Walt Whitman, “miracles”

The American contempt for statues and ceremonies, the boundless impatience for restraint…

Walt whitman, “Song of the Broad-axe”

I exist as I am, that is enough. If no other in the world would be aware I sit content. And if each and all be aware I sit content.

walt whitman, “Song of myself”

I am not the poet of goodness only, I do not decline to be the poet of wickedness also.

walt whitman, “song of myself”

If any thing is sacred the human body is sacred.

Walt whitman, “i sing the body electric”

NOTES: Numerous editions exist between the 1855 and 1892 (deathbed) edition. It’s available for free on Project Gutenberg at: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1322

In Homage to Leaves of Grass

You're my Analects,

my Gita,

my Dao De Jing,

my sutras,

my Meditations,

and my Republic

all rolled into one.

You are the scripture by which I live.

You present a path to that rare place:

extreme confidence

which tears no one down,

but, rather, lifts all.

You achieve this by crushing

the ordinary.

Nothing is common.

Everything is a miracle.

(Even those leaves of grass

you repeatedly reference.)

No one is so rough

or promiscuous

or simple

as to be lowly.

Your author's unbridled enthusiasm

glowed with the insane confidence

of an adolescent boy,

but his awesomeness was never gained

by subtracting from others.

Rather by seeing the bright, beautiful spark

in each body,

mind,

pair of hands,

& burdened shoulder.

You are America,

the America we want to be.

The America that labors,

but which takes time to see

its natural wonders.

The America that heard what Jesus said,

and became less excelled at stone-throwing,

and more at cheek-turning.

The America that could see beyond dogma

and hard-edged tribalism,

and could learn from all the

grand & glorious people

who reached its shores --

So that we could be the best version of ourselves

through the strengths of all of us,

and not be stymied by missing

the great beauty & knowledge

among us.

You pair away the extraneous burdens

which tax the mind,

and show us what the world looks like

unfiltered.

You teach one to see a beauty

that is so well hidden

that its own possessor doesn't

recognize it.

You are the song of a life well lived.

BOOK REVIEW: Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

There are a number of editions of this collection of poems, as Whitman apparently continued to revise it right up until his death. The 1855 edition is popular but there is a “Deathbed Edition” which–as the name implies–is the closest thing to a final draft that exists.

Back in the day (the late 19th century), this was considered racy and controversial stuff, and the collection got Whitman fired from is civil service job as well as a great many vitriol-filled reviews. Like the works of Emerson and Thoreau, with whom Whitman shared some beliefs, it was also controversial in that the poem put man at the fore and religion was shunted out of the picture. (Trust in yourself and don’t blindly follow anyone was still a heretical notion among many at the time.) This isn’t to say that Whitman eliminated spirituality from his work (any more than Emerson did), references to the soul are commonplace—but it’s a mystic spirituality. There were features outside the “prurient” and religious that angered many, such as Whitman’s shining of light on the barbaric institution of slavery. However, today Leaves of Grass is considered one of America’s greatest and most beloved works of poetry, and for good reason. It beautifully reflects an America that was changing, an America subject to a new era of ideas both from science and from distant lands.

It should be noted that this is a life’s work. If you are expecting a typically thin poetry collection, you will be in for a surprise. Leaves of Grass is of a page count normally reserved for histories and epic novels. The collection consists of 35 “Books” that are quasi-themed sub-collections of poems. Individual poems vary greatly with some being only a few lines and some running for pages. Most of the poems are free verse, though there are sections that display a meter (specifically iambic pentameter.) Free verse is poetry without meter or rhyme. If you didn’t know there was such poetry, you may want to work through your Doctor Seuss before you crack open a tome like this one.

There are a few themes that are repeatedly revisited. One idea that made the collection so controversial is that it exalted in the human form and the physicality of humanity. In recent years, a lot of discussion of this work revolves around whether Whitman was or wasn’t homosexual or bisexual. Not that it matters, but the fact is there is a dearth of information about what form of sexuality Whitman practiced—if any, but one can imagine why people wondered. Whitman writes descriptively about both the male and female forms, and was not shy about verse that suggested lying with this gender in one poem and the other in the next. The poem “I Sing the Body Electric” is probably the most famous example of Whitman’s discussion of the body.

However, perhaps the most striking theme is a celebration of America, both in its natural state and as it was shaped by the people who settled there. In multiple poems one sees long strings of description and exposition about the various states of the United States. Whitman paints pictures of the nation as a collage showing the variations among its constituent parts. To a lesser extent, he does the same for the world (e.g. see Book VI.)

I enjoyed this collection, although I will admit I read it a bit here and a bit there over a long time period. I, therefore, probably missed some of the depth of meaning coming from how the poems were arranged. Maybe someday I’ll have time to go back and read it once more. However, the beauty of this collection is that it’s so many different things. It meanders like a river, and peers overland with an eagle-eyed view. It offers scenes that are like a hard-boiled work of film noir and ones that are like Ansel Adams pictures. It’s not anti-god, but rather about the god within, or the god within the blade of grass. Leaves of Grass offers brilliant turns of phrase, bold descriptions, and always interspersed with the author’s personal philosophy.