Last week I attended a five-day workshop on pranayama, the breathing exercises practiced in hatha yoga. (Yes, I’m aware that that definition may be a radical oversimplification to many.)

Breath is like water. It’s easy to take for granted as long as it’s unimpeded, but the moment it’s cut off life is miserable–not to mention short. (If you’ve never been at an altitude that your body wasn’t adjusted to, this may not seem profound, but trust me.) We reduce breath to an autonomic function–mindless and effortless. It’s easy enough to do this if one doesn’t have an interest in getting control over one’s emotional life or one’s health.

FUN FACT: Exhalation inhibits the firing of the amygdala–two structures in the brain that are partially responsible for our experience of fear. Ergo, elongating exhalations may diminish the expression of fear. [This isn’t a fact that I learned at the workshop, but was something I recently read in the book Zen and the Brain, which is a neuroscientist’s explanation of the nervous system and the effect of meditation on it.]

The workshop was educational and offered plenty to work on as I expand the pranayama portion of my practice. Here are a few of the takeaways I brought from the workshop:

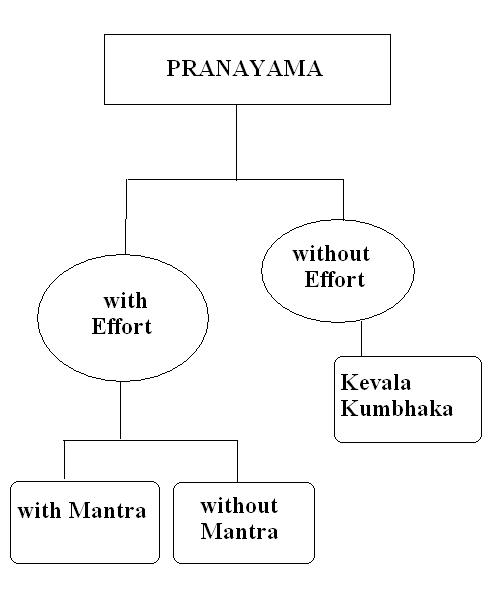

1.) There’s a thorough system of classification of the various pranayama practices. This might seem self-evident, but it’s not something I’d thought of before.

Classification begins with the tree above, but there’s much more to it. For example, one might group practices lying under the “without mantra” box as vitalizing (e.g. Bhastrika) or tranquilizing (e.g. Sheetali/Sheetkari.) One can also classify pranayama by whether there’s a retention of breath or not, and–if so–whether the retention is done with air in (Antar Kumbhaka), air out (Bahya Kumbhaka), or both (Sahit Kumbhaka.)

Classification begins with the tree above, but there’s much more to it. For example, one might group practices lying under the “without mantra” box as vitalizing (e.g. Bhastrika) or tranquilizing (e.g. Sheetali/Sheetkari.) One can also classify pranayama by whether there’s a retention of breath or not, and–if so–whether the retention is done with air in (Antar Kumbhaka), air out (Bahya Kumbhaka), or both (Sahit Kumbhaka.)

2.) [Related to lesson # 1.] Some of my favorite pranayama aren’t necessarily considered pranayama. Nadi Shodhana (alternate nostril breathing) is classified as a shatkarma (cleansing practice) rather than a pranayama by many. Furthermore, some think of kapalbhati (forced exhalation breathing) more as a shatkarma–though many accept that they can be classified either way. Certainly, it’s more important that you do it than put it in the right box, but I found it interesting nonetheless.

3.) Ghee is to yogis as duct tape is to a handyman. It’s a readily available multi-purpose tool. But seriously, I learned that hot milk and ghee–for some reason–have different characteristics in the body than regular cold milk. One wants to minimize mucus producing foods when one does a lot of pranayama for obvious reasons. (Blowing snot bubbles is neither dignified nor sexy.) So it came as a surprise when ghee and warm milk were suggested foods. (Milk, when taken cold, is about as mucus-producing a food as there is.)

3.) Ghee is to yogis as duct tape is to a handyman. It’s a readily available multi-purpose tool. But seriously, I learned that hot milk and ghee–for some reason–have different characteristics in the body than regular cold milk. One wants to minimize mucus producing foods when one does a lot of pranayama for obvious reasons. (Blowing snot bubbles is neither dignified nor sexy.) So it came as a surprise when ghee and warm milk were suggested foods. (Milk, when taken cold, is about as mucus-producing a food as there is.)

4.) I learned why I can hold my breath so long after kapalbhati (or bhastrika) breathing. (Kapalbhati is a breath in which the exhalation is forced out; in bhastrika both the inhalation and exhalation are forced [pumped]–i.e. these are hyperventilating breathes.) I noticed a while back that as I practice kapalbhati, doing internal retention afterward was easy to hold for a long time. This is probably one of the most counter-intuitive facts I’ve experienced in practicing breathing exercises. The body has shed a bunch of carbon dioxide and has time and capacity to build up more without the body responding severely. It should be noted that the feeling of suffocation what we experience as being “short on breath” isn’t a lack of oxygen. It’s an excess of carbon dioxide. [One should also note that the reason that one needs to exercise great caution and graduality with these breathing methods–i.e. the reason that people have been known to pass out–is that the body reacts severely to carbon dioxide levels that are outside the appropriate ranges.]

5.) Diet is considered more important in starting a pranayama practice than in starting an asana (postural) practice. The basis of this statement is that one of the most prominent hatha yoga manuals (e.g. Hatha Yoga Pradipika) recommends dietary considerations for those beginning a serious pranayama practice, but it makes no similar statements with regard to beginning an asana practice. This doesn’t mean that what / when one eats isn’t important for postural practice. Anyone who’s ever eaten a heavy meal too close to an intense asana practice will know that it’s not true that food is irrelevant for asana practitioners. However, there seems to be a belief that many specific foods can be quite detrimental to pranayama practice–and a few really mesh well with such a practice.

FUN FACT: Conscious breathing stimulates the Vagus nerve, and the Vagus nerve is crucial in the functioning of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)–i.e. advancing the “relaxation response” or “rest & digest” functions. Therefore, conscious breathing practices can help one to be healthier because PNS activity supports healing functions.

6.) There’s an established sequence of advancement that can be used across many different breathing exercises. One will see breath ratios that consist of up to four numbers. (e.g. 1:1 means that inhalation and exhalation are the same length (whatever that length may be, it will vary by person); 1:2:1 means that one internally holds the breath for twice as long as one does the inhalations and exhalations; and 1:1:1:1 means that one will inhale, internally retain, exhale, and externally retain all for the same length.)

Note: the counts that those numbers represent can and should increase over time–e.g. a 1:2:1 ratio may represent a six count inhalation/exhalation with a twelve count retention or it could be an eight count inhalation/exhalation and a sixteen count retention.

The aforementioned sequence is 1:1, 1:2, 1:1:1, 1:2:1, 1:2:2, and 1:4:2.

Happy breathing.