Martial arts cinema ranges from the horrible through the campy to the excellent. There is one ever-present risk facing this genre. That is, like porn, movie makers may conclude that viewers aren’t watching for character or plot so they might as well just focus on the action. When they do that and then they blow the action– well, that’s when it’s painful to watch. By numbers, most of this genre probably falls into that category. However, sometimes they get it right.

Of course, it’s not always clear what should be categorized as a martial arts film, given many cross-genre romps. The Matrix is science fiction, but it’s also a kung fu flick. The Bourne trilogy films are spy thrillers, but their characteristic gritty hand-to-hand combat sequences are integral to the films. I’ve tried to focus on films that one would unambiguously categorize as martial arts cinema (though anything by Kurosawa is likely to be considered mainstream cinema.)

I also, admittedly, display several of my own biases. I prefer films that avoid over-the-top superhuman choreography. I don’t want to say that I prefer realism. None of it is realistic, but there’s a vast difference between Jackie Chan’s choreography and that of The Curse of the Golden Flower. Still, I do include Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon and Kung Fu Hustle, which both rely heavily on wires and superhuman feats. I also like period pieces as opposed to modern-day films. Of course, characters with charisma also get my attention, but I don’t think I’m unique in that regard.

5.) Enter the Dragon

Enter the Dragon is Bruce Lee’s last film, and features Lee as a Shaolin practitioner cum secret agent. The film reminds me of the Ian Fleming novel You Only Live Twice in that it’s about a person being tasked to infiltrate an evil mastermind’s sprawling lair not because it makes logical or reality-based sense, but rather because the proposed infiltrator is just that damn good.

4.) Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon

This is undoubtedly the most critically acclaimed of the films on the list. It was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar in 2000, and while it did not win in that category, it did take four Oscars that year. It’s in a class of film that includes Curse of the Golden Flower and Hero that are known for stunning cinematography and historical settings. (Unfortunately, these films are also marked by an insanely excessive use of wire-work for my taste.) This film includes a romantic component as well as the fight to possess a sword called Green Destiny. As is mandatory for Kung fu films, there’s a martial arts master whose death must be avenged.

3.) The Legend of Drunken Master (aka Drunken Master II)

Jackie Chan plays a bumbling young man who is, ironically, a master of Kung fu when completely inebriated. The plot revolves around a mix up between an agent who is trying to steal a valuable artifact and Chan’s character who is trying to smuggle ginseng to avoid paying duty on it. Incredibly, the artifact and ginseng are packaged identically, and the thief ends up with the ginseng and Chan’s character with the artifact. It’s Chan at his best, with all the comedy and creative choreography that one would expect.

2.) Hidden Fortress

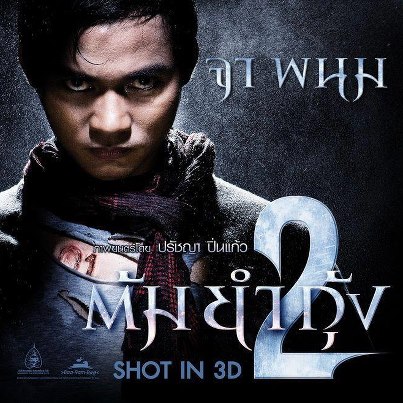

I’m not including this just to prevent a Chinese sweep. (On that note: I’ve heard the Thai Ong Bak films are quite good, but I haven’t gotten around do seeing any of them.) Anyway, there are some excellent Japanese period films that involve many combat sequences that are not over-the-top. Of course, Akira Kurosawa dominates in this realm. There are other Kurosawa films, such as Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, or Ran that could equally well be included. Hidden Fortress is probably best known to American movie buffs as a major influence on George Lucas in the making of the first Star Wars film. Hidden Fortress is a about a General (played by portrayer-of-samurai-extraordinaire Toshiro Mifune) who must escort a princess and her family fortune cross-country to safety. Of course, as in every hero’s journey, there are many challenges to be confronted.

1.) Kung Fu Hustle

This comedy is set in the gang-ridden slums of 1930’s Shanghai. A tenement complex is assailed by the gangs. However, the residents offer some surprising resistance in the form of unexpected apartment-dwelling kung fu masters. Unlike Jackie Chan’s down-to-earth comedies, this one is almost cartoon-esque. It features a cast of anti-heroes that keeps the film interesting, and the protagonist has a strong narrative arc.