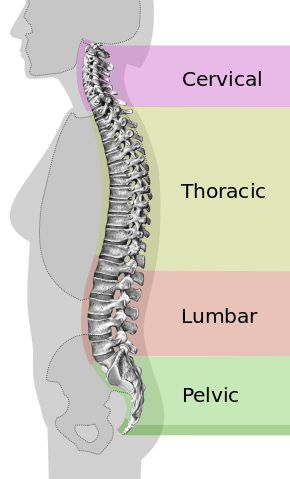

Hyperkyphosis (a.k.a. Excessive Thoracic Kyphosis, “Dowager’s Hump”, or often just called Kyphosis) is an excessive outward curve of the thoracic (chest) region of the spine. There are many causes and contributors to this problem, but–for the purposes of this post–I’ll be focusing on postural kyphosis. There is a natural curvature in this part of the spine that is healthy. However, as is also true of the lumbar spine, the amount of curvature can become excessive, leading to a number of health conditions.

5.) Hyperkyphosis increases the risk of injurious falls in older people. Having one’s head forward, when combined with a lack of capacity to respond quickly to loss of balance, makes it more likely one will fall and hurt oneself.

Source: Kado, D.M., et. al. 2007. Hyperkyphotic posture and risk of injurious falls in older persons: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. Vol. 62: 652-657.

4.) As far as the muscles of your upper back and neck are concerned, an 11 pound head can weigh 40 to 50 pounds when it’s forward positioned. Hyperkyphosis and forward head position tend to go hand in hand. If you purposely slump your back you’ll see why.

Source: Hansraj, K.K. 2014. Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of head. Surg Technol Int. Vol. 25(Nov): 277-279.

3.) There is reason to believe the young are becoming more prone to hyperkyphosis in conjunction with “text neck” from spending lots of time slumped over their phones.

Source: in addition to the Hansraj journal article above, see also: Ward, Victoria.2015. Children ‘becoming hunchbacks’ due to addiction to smart phones. The Telegraph. October 16. Online edition; last accessed Nov. 7, 2017.

2.) Yoga can help reduce hyperkyphosis. A test group who practiced hour-long sessions of yoga three days a week for 24 weeks showed an improvement in the flexicurve angle of kyphosis.

Source: Greendale, G.A., et. al. 2013. Yoga decreases kyphosis in senior women and men with adult onset hyperkyphosis: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 57(9): 1569-1579

1.) Older individuals may be at risk for fractures, particularly when doing spine flexing movements, but careful use of spinal extensions (e.g. hands free cobra or superman shalabasana [locust]) can build strength and reduce fracture risk.

Source: Katzman, W.B., et. al. 2010. Age-related hyperkyphosis: its causes, consequences, and management. J Orthop Sports Ther. 40(6): 352-360