Anecdotes of the Cynics by Robert F. Dobbin

Anecdotes of the Cynics by Robert F. DobbinMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon.in Page

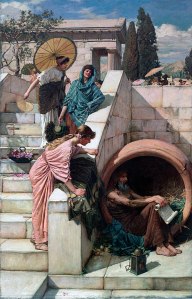

This is a collection of brief stories and sayings from famous Cynic philosophers – notably, Diogenes of Sinope, Crates of Thebes, Hipparchia, and Bion. It opens with the longest piece, a dialogue [allegedly] by Lucian the Cynic advocating the Cynic’s minimalist approach to life. [Cynics were ascetics who shunned customs and cultural conventions and thus often ran afoul of the conservative societal base / rubbed people the wrong way.] The dialogue uses Socratic method, but also contains prolonged exposition. [Not like the Platonic dialogues in which Socrates tends to ask brief questions and attempts to demand brief answers – granted not always successfully.] However, most of the pieces are just a paragraph or two brief excerpts.

Most of the entries report on what various Cynics said or did, though there are a few that are biased commentaries of non-Cynics about these “dog philosophers” – e.g. there is a Catholic tract denouncing the Cynics while talking up Paul. [It reads as though the early Christian church (which was teaching Jesus’s ideas, including: in part, the virtues of poverty, of simplicity, and of a lack of deference to the world of men) might have been concerned about being outcompeted.]

There’s not a tremendous amount that remains of direct Cynic teachings, and so a book like this is a way to get a taste of the highlights. Just as Buddha found that extreme forms of ascetism didn’t yield the optimal result, Cynicism lost ground to the upstart school Stoicism, which borrowed some Cynic ideas while jettisoning the most extreme aspects of the philosophy.

One can find these stories in old public domain sources such as Diogenes Laertius’ (no relation) “Lives of the Eminent Philosophers,” but this is a good way to get the condensed version without too much extraneous information.

View all my reviews