A History of the World in 6 Glasses by Tom Standage

A History of the World in 6 Glasses by Tom Standage

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Get Speechify to make any book an audiobook

Standage’s book takes a fascinating look at the effect that six key beverages had in the unfolding of world events, as well as how the beverages themselves made friends and enemies. The drinks in question are beer, wine, spirits, coffee, tea, and cola. There are two chapters for each of these drinks. They follow a chronological order based upon when the respective drink rose to prominence, but within the discussion there is overlap of time periods. For example, both the chapters on spirits and tea consider the effect of those beverages on the American Revolution (i.e. the Whiskey Rebellion and the Boston Tea Party, respectively.)

As the author points out, there’s a natural subdivision to the book, which is that the first three beverages are alcoholic and the last three are caffeinated. There’s another way of looking at it, and that’s the means used to achieve a drink that wasn’t a health hazard. The first three drinks achieve germ-killing by fermentation, the next two by boiling, and the last through technology.

The era of beer is associated with the Agricultural Revolution and the growing importance of cereal grains. Geographically, the region of focus is the Fertile Crescent and Egypt. Among the more interesting points of discussion is the role of beer (along with the related commodities of cereal grains and bread) in the development of written language.

The era of wine is associated with the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. Readers of the classics will be aware that wine was much celebrated among the Greeks and Romans, so much so that they developed gods of wine in their mythologies (Dionysus and Bacchus, respectively.) Of course, wine played no small role in Christian mythology as well–e.g. Jesus turns water to wine.

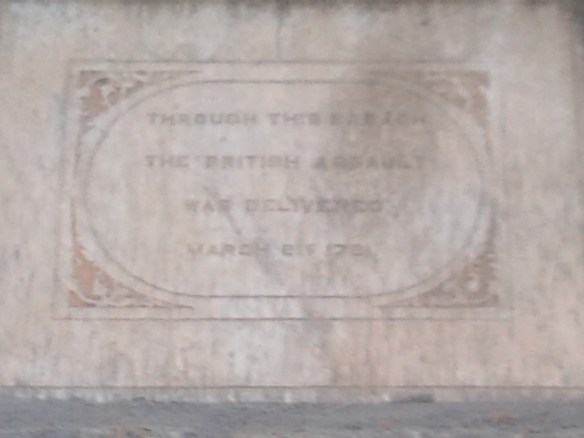

Spirits are related to the Colonial period, though they were first developed much earlier. The author emphasizes that these were the first global drinks. While beer and wine were robust to going bad, they could spoil in the course of long sea voyages.

Alcohol of all kinds has always attracted opposition. This conflict, of course, owes to the fact that people under the influence of alcohol frequently act like idiots. One might expect that the transition to discussion of non-alcoholic beverages would correspond to the end of controversy, but that’s not the case. Each of the beverages brought controversy in its wake. There were attempts to ban coffee in the Islamic world where its stimulative effect was conflated with intoxication. Coca-Cola became associated with capitalism and American influence, and drew its own opposition because of it. It seems there’s no escape from controversy for a good beverage.

The most fascinating discussion of coffee had to do with the role of cafés as corollaries to the internet. Centuries before computers or the internet as we know it, people went to cafés to find out stock values and commodity prices, to discuss scholarly ideas, and to find out which ships had come and gone from port.

The role of tea in world history is readily apparent. Besides the aforementioned Boston Tea Party, there were the Opium Wars. This conflict resulted from the fact that the British were racking up a huge tea bill, but the Chinese had minimal wants for European goods. Because the British (through the East India Company) didn’t want to draw down gold and silver reserves, they came up with an elaborate plan to sell prohibited opium in China in order to earn funds to pay their tea bill. Ultimately, Britain’s tea addiction led to the growing of tea in India to make an end-run around the volatile relations with China.

The book lays out the history of Coca-Cola’s development before getting into its profound effect on international affairs. A large part of this history deals with the Cold War years. While Coca-Cola was developed in the late 19th century, it was really the latter half of the 20th century when Coke spread around the world—traveling at first with US troops. The most interesting thing that I learned was that General Zhukov (a major Soviet figure in the winning of World War II) convinced the US Government to get Coca-Cola incorporated to make him some clear Coca-Cola so that he could enjoy the beverage without the heart-burn of being seen as publicly supporting an American entity (i.e. it would look like he was drinking his vodka, like a good Russian should.) General Zhukov was perhaps the only person to stand in opposition to Stalin and live (the General was just too much of a national hero to screw with.)

There’s also an interesting story about how the cola wars played out in the Middle East. Both Coke and Pepsi wanting access to the large Arab market, and were willing to forego the small Israeli market to pave the way for that access. When Coke finally had to relent due to public outrage and accusations of anti-Semitic behavior, Pepsi slid in and followed Coca-Cola’s policy of snubbing Israel in favor of the Arab world.

I enjoyed this book, and think that any history buff will as well. One doesn’t have to have a particular interest in food and beverage history to be intrigued by stories contained in this book.