The Way of The Iceman: How The Wim Hof Method Creates Radiant Longterm Health–Using The Science and Secrets of Breath Control, Cold-Training and Commitment by Wim Hof

The Way of The Iceman: How The Wim Hof Method Creates Radiant Longterm Health–Using The Science and Secrets of Breath Control, Cold-Training and Commitment by Wim Hof

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Wim Hof is often presented as a freak of nature. If you’re flipping through the science channels, you might see a segment that shows him subjecting himself to extremely cold temperatures with no ill effects. This book is an attempt by Hof, and co-author Koen De Jong, to counter the proposition that he’s some sort of mutant (or—worse–that his demonstrations are cons) by offering a method by which anyone can achieve the same feats. It should be noted that long before Hof and YouTube came on the scene, there were people [notably Taoist and Tibetan Buddhist monks] performing similar acts.

Hof’s method (called the “Wim Hof Method” or WHM herein and in this book) consists of three components: cold training, breath exercises, and commitment building. The book explores this three-legged stool from both the scientific and practical dimensions. There’s one chapter on each of these elements that describes what it does to the body and how it contributes to well-being, and later chapters both describe what scientific studies have found so far and outline the approach by which the reader can explore the WHM on their own.

There’s a lot of front matter in this book (two forwards, a prologue, and an introduction), but the book more-or-less consists of seven chapters. The first of these is a mini-bio of Hof. It describes a fascinating event in Hof’s youth in which he was exposed to cold, as well as his travels to India in an attempt to find a yoga teacher. [As is the case with most people who come to India seeking to find that quintessential guru—i.e. a half-naked, weather-beaten, and forehead paint-streaked classical guru—he found that he had to wade through a sea of charlatans and shysters while never finding the true masters who are likely hidden away in caves in the Himalayas. Note: this is not to say that one can’t find excellent yoga instruction in India but it’ll likely be by someone fully clothed and not someone smoking pot on a ghat in Varanasi.] This resulted in Hof taking an experimental approach in which he studied the effects of various activities on himself (and such experimentation is what he advocates for others as well.) It should be noted that Hof didn’t invent this method from scratch—e.g. the breath component is based on Tibetan Tummo meditation.

As mentioned, Chapters 2 through 4 explore the three components of the WHM, i.e. cold training, breath exercise, and commitment building, respectively. These chapters describe the science of how these three elements generally (as opposed to a later chapter that describes studies in more depth) act upon the body. The commitment section describes a number of arduous feats such as climbing Kilimanjaro in a T-shirt and shorts, but also describes the role of diet (with particular emphasis on the fast-5 diet which is similar to, but not precisely, what Hof came to practice organically.)

Chapter 5 dives more deeply into the science than does the preceding chapters, and focuses on the studies in which Hof has participated in his attempt to facilitate a better understanding of his method.

The penultimate chapter suggests what the WHM might do for people in various classes, including: healthy people, athletes, and people suffering from various physical and mental ailments. With respect to the latter, there is discussion of exemplary cases as well as the possible means by which the training might act.

The final chapter is a brief outline of how the WHM can be put into practice by readers. There is also a sample log by which practitioners can chart their experience.

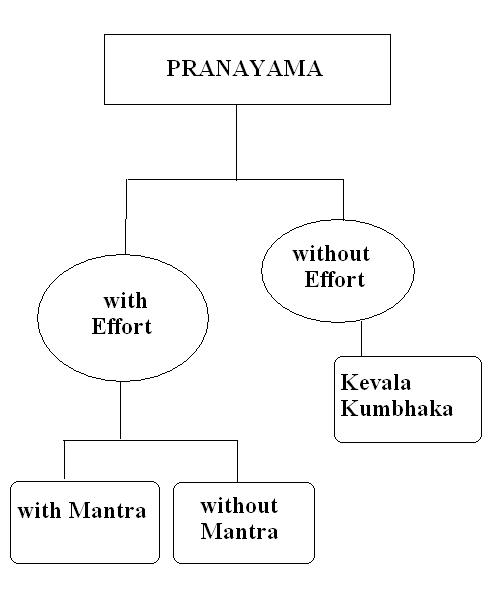

There are a range of graphics including line diagrams and photographs. Most of the photographs are inspirational shots of Hof in action, but there are diagrams and other graphics used to convey scientific ideas. There’s a recommended reading page as well as a works cited page. Both lists are small and confined to a few key sources of information, with the latter being the more scholarly works. There is also a glossary that may prove handy for some readers.

This book is illuminating and many stand to benefit from it. I found the approach of the authors to be sound; it’s basically “see for yourself.” This book could easily have been a sales brochure, and in some ways it is, but the fact that it emphasizes the science and the suggestion that the reader try the practice lends credibility. I’d highly recommend this book for anyone who wants to expand and explore the limits of their capability.