Apology by Plato

Apology by Plato

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Amazon page

Apology is Plato’s account of the trial of Socrates. This brief work presents Socrates’ defense of himself as well as his reaction to the death sentence verdict against him. Of course, it is all through the lens of Plato, as Socrates left us no written works.

Socrates was charged with impiety and corruption of the youth. He acknowledged both that he was eloquent and that he was a gadfly of Athens (the latter being a role for which Socrates believes he should be valued.) However, he denied both of the formal charges.

Socrates refuted the charge of corrupting the youth first by denying that he had taken money in exchange for teaching. Taking money was a component of this charge. Socrates’ claim is supported later when Socrates tells the court that he can only afford a very small fine, even in the face of the alternative–a death sentence.

Socrates says that he sees nothing wrong with taking money for teaching–if one has wisdom to share. Socrates says that he has no such wisdom, and suggests the philosopher/teachers that are taking money aren’t in error for taking money, but rather because they really don’t have wisdom themselves.

This is summed up nicely by this pair of sentences, “Well, although I do not suppose either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is–for he knows nothing and thinks he knows. I neither know nor think I know.”

While Socrates raised the ire of the Athenian leaders with what they no doubt believed to be his arrogance, in fact it wasn’t that he thought himself wiser than they, but that he thought they were deluded in thinking themselves wise.

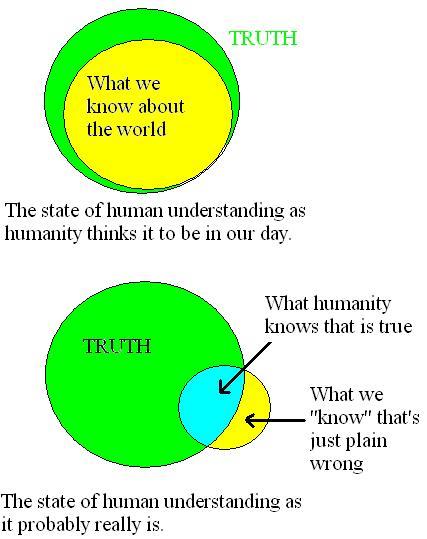

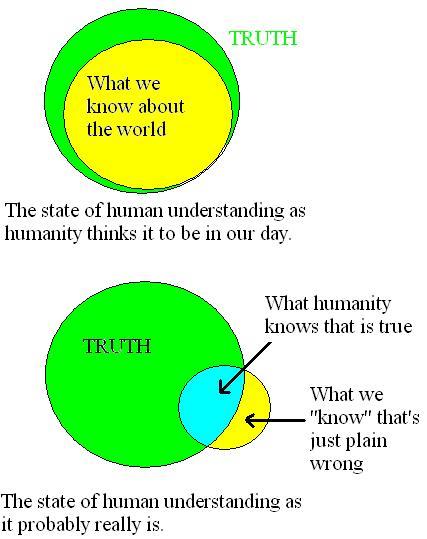

Socrates’ lesson remains valid today. It is the scourge of all ages to think that have finally attained true understanding of the world. Our posterity may know more, but we know all of the essentials and are rapidly converging on a complete picture of our world. We think our generation to be humanity’s sage elders, when, in fact, we are the impetuous teen whose growth spurt has made him cocky. I would propose to you that in all likelihood, even today, the sets of “that which is true” and “that which humanity ‘knows'” form a classic interlinking Venn Diagram. That is, some of the body of knowledge that we take to be proven true is, in fact, false. This occurs because we cannot accept that there are things we are not yet prepared to know, so we use sloppy methodology to “prove” or “disprove.” This one reason we have all these conflicting reports. E.g. coffee is good for you one week, and carcinogenic the next.

Socrates uses the method that today bears his name, i.e. the Socratic method, to challenge the arguments of Meletus, the prosecutor. The Socratic method uses questions as a device to lead the opposition to a conclusion based on premises they themselves state in the form of their answers. Socrates proposes that if it is he alone who is intentionally corrupting the youth, they would not come around–for no one prefers to be subjected to evil rather than good.

Socrates denies the suggestion that he does not believe in the gods, and in fact indicates that the very suggestion by virtue of the charges against him is a contradiction. What Socrates is guilty of is encouraging those who come around him to develop their own thoughts on god, and not to subordinate their thought to anyone–an idea the leaders found disconcerting.

Socrates goes on to say why he is unmoved by the death sentence. He wonders why it is thought he should beg and wail, when he doesn’t know for sure that an evil is being done against him.

The moral of the story is that those in power fear and will attempt to destroy advocates of free thinking.

This book should be read in conjunction with a couple other Platonic Dialogues, Crito and Phaedo.

View all my reviews

Share on Facebook, Twitter, Email, etc.

Menexenus by Plato

Menexenus by Plato